“Evolution is the central theme of biology – a common thread running through every chapter of this book.” …so proclaims the introduction to Campbell, a widely used scientific textbook. The preceding sentences explain: “Evolutionary processes account for both the similarities and the diversity of organisms. Traits shared by two species are due to their descent from a common ancestor; differences between species result from natural selection gradually modifying traits […] like a machine being rebuilt while continuously running.” [1]

This passage was penned by a natural scientist. An engineer, however, might scratch their head at the image of a “machine being rebuilt while continuously running,” since such a thing doesn’t actually exist. Integrating novel constructions into an existing, functioning system is quite problematic (and “half-finished” building stages aren’t visible in fossils either) – but that’s just an aside.

Many biologists view the ever-present evolutionary process as the “red thread” connecting all branches of the “life sciences.” A now-famous quote states: “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” [2]

After nearly thirty years of working in biological research, I can only marvel at such a statement. The functions and interrelations we investigated in various projects made perfect sense in their complex interplay and ideally revealed potential for therapeutic intervention – which we aimed for in the development of pharmaceutical agents. What I never encountered during this time, however, was any relevance of speculating about the possible origin of our target structures. The “light of evolution” seems to shine elsewhere …

Indeed, the common thread in the form of an evolutionary history tracing all life back to a common origin is completely irrelevant to the applied sciences. Observable recent changes (microevolution), on the other hand, play a significant role in fields like ecology, microbiology, virology, immunology, and genetics. However, the historical extrapolation – the overstretching of the observed principle of limited change into a notion of boundless transformability from the origin onward – is not needed in practical research. [3]

The search for patterns, meaning, and logical connections is deeply human. One could even argue that rationality and the quest for meaning can only exist if there’s an overarching, rational originator. Nonetheless, it’s widely believed that the idea of a natural evolutionary history is the only rational concept of origin. After all, our experience and observations suggest that complex things don’t appear suddenly, but develop over time (as a plant from a seed or an animal from an egg). The historical record seems to support this. As far back as traditions go, we find ideas of ancestry and development competing with creation narratives, which, when detached from biblical revelation, often devolved into myth in pagan idolatry.

Both concepts ultimately face the problem of the “primordial beginning”: what was there before anything existed? When cosmologists today speak of “nothing” at the beginning [4], they usually mean a “quantum vacuum” or “quantum foam.” But that’s not nothing!

Nothing is the absolute absence of anything. If there really was nothing at the beginning, the origin of something must have been supernatural, because where there is no “nature,” there are no natural laws and no “natural processes.” A naturalist who refuses to follow this logical conclusion to a supernatural origin ends up believing in “quantum fluctuations from eternity,” just as a theist believes in a “God from eternity.” Neither is comprehensible to our minds.

It is rightly pointed out that experience shows every living being originates from a very similar being. Therefore, biological similarity, which can be expressed in many ways, is interpreted as evidence of common descent.

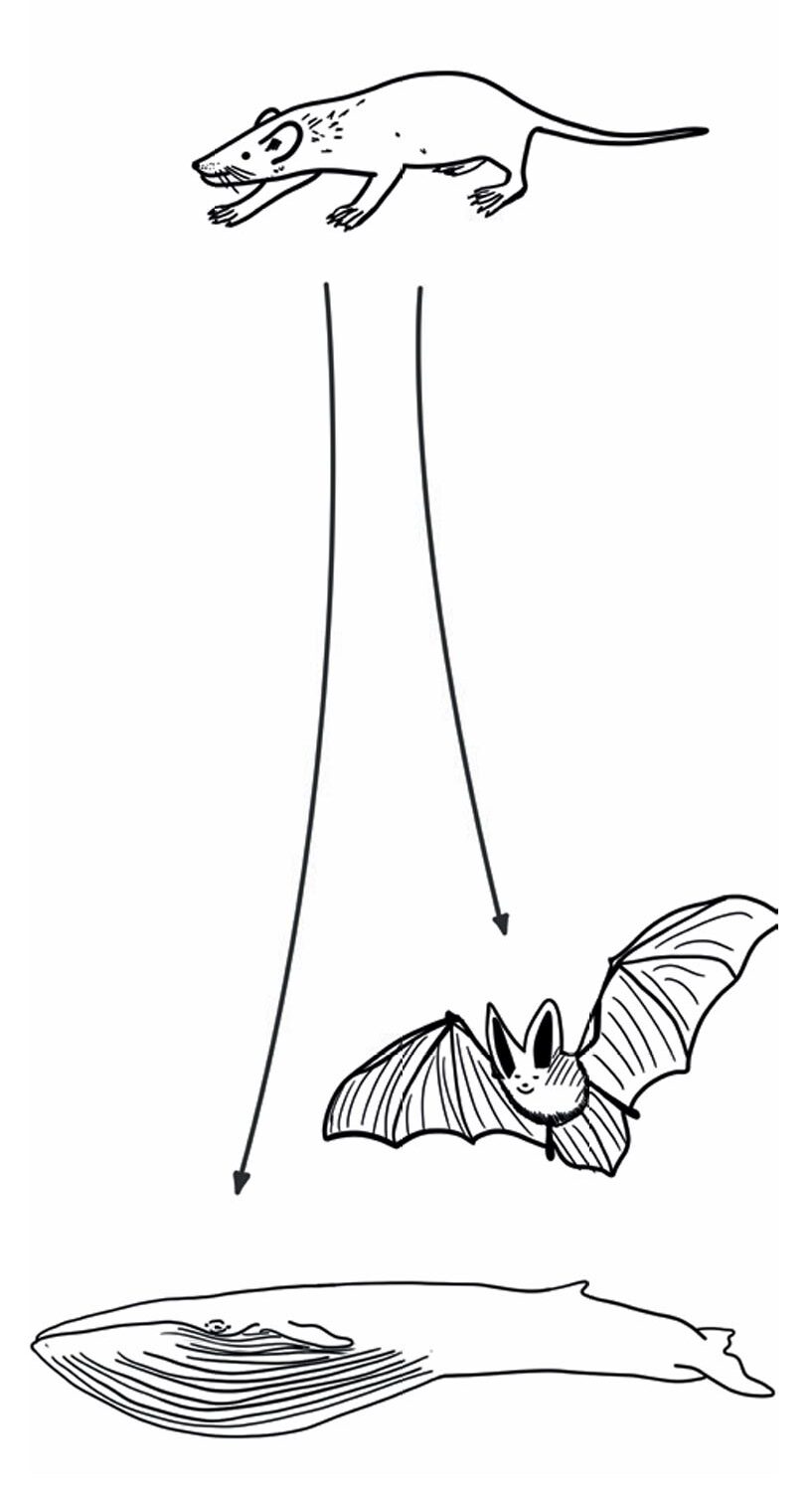

But appealing to logic and intuition here treads on thin ice, because the idea that such different animals as a blue whale and a bat share a common ancestor that looked like a rat does not match our simple expectation of similarity. Rather, we observe that descent always results in very similar offspring. The argument would be coherent if one could trace a finely graded transformation in the sequence of increasingly dissimilar fossil ancestors – but that’s not the case!

Today, phylogenetic reconstruction is increasingly less about external similarities between organisms, as studied and assessed by anatomists and taxonomists, and more about biochemical and especially genetic similarities. Full genome sequencing allows us to quantify similarity – often with surprising results.

The “genetic relationship” between humans and chimpanzees, for instance, was long claimed to be 98–99% – still stated in many publications – although sequence data now show only about 84% similarity. The “2% myth” is outdated, and 16% genomic divergence paints a different picture. Recent mouse studies – despite little outward similarity to humans – yield similar divergence. This slightly corrected perspective is just one puzzle piece, but it raises the general question: What does percentage similarity actually mean?

A cucumber, a jellyfish, a cloud, and a Bud all consist of about 95% water, and are thus very similar chemically. But what does that imply? One must consider which level of entities is being compared. At the most fundamental level, all material things consist of the same atomic and subatomic building blocks – making them 100% similar. At higher levels, differences grow. The aforementioned finding that the mouse genome is as similar to the human genome as the chimpanzee genome is could also suggest that genome sequencing lies too low on the structural hierarchy. At higher levels (anatomy, brain organization, perception, communication, and learning behavior), there is indeed greater similarity between humans and chimpanzees than between humans and mice. The idea of ape-like ancestors would not be unreasonable based on form comparison alone – if humans descended from animals.

The crucial step is to move even higher. At the highest level, there is no similarity at all. On one side, we have “spirit” (God and His spirit-endowed creatures – angels and humans – who share similarity among themselves), and on the other side, “non-spirit,” the rest of creation.

So far, there is no plausible model explaining the origin of spirit (and spiritual traits like consciousness, will, morality, and language) from non-spirit. Upon closer inspection, the problem of this transition proves to be just as insoluble as the origin of matter from non-matter, life from non-life, or information from non-information. This explanatory deadlock is often cloaked in vague terms like “epiphenomenon” or “emergence,” creating an illusion of inevitability. This leads to optimistic claims: “With 10^500 universes in the ‘multiverse,’ the ‘right’ one with matter must exist; as soon as there’s liquid water on a rocky planet, life can emerge; a sufficiently complex brain will develop self-awareness and consciousness.” – None of these assumptions can be scientifically substantiated.

The interpretation of similarity as evidence of common descent also rests on an analogy. Today, we observe descent within species and apply this to the past. But that’s not the only conceivable analogy. It is equally “intuitive” to recognize the “handwriting” of a common creator in the similarities. That, too, matches our experience. Similar designs are the work of the same planner, builder, originator, or architect. Experts can identify authentic old master paintings by studying brushwork. Not just the stroke, but also how paint is applied and blended are signature features of an artist. Similarly, distinctive stylistic traits can be found in architects, composers, poets, and authors.

The unifying element in this perspective is the ingenious design of all living things. This obvious feature is acknowledged even by a leading advocate of atheistic naturalism, who remarked: “Biology is the study of complicated things that give the appearance of having been designed for a purpose.” [5]

However, he considers this appearance to be mere illusion. Honest naturalists should be troubled that we cannot speak or think about biological systems without attributing to them goal, purpose, and meaning – which cannot exist in a universe ruled by chance.

Let us revisit the metaphor of the “common thread.” It originates (in Germany) from the German poet Goethe, who explained it as follows: “We hear of a special feature in the British Navy. All ropes in the royal fleet, from the thickest to the thinnest, are spun with a red thread running through them, which cannot be removed without unraveling the whole, and by which even the smallest pieces are identifiable as belonging to the Crown.” [6]

It’s interesting that this idiom not only suggests unity and coherence through a common feature, but also points to ownership. Not common descent, evident in similarities, but the signature of the same Creator, evident through highly intelligent design, extravagant diversity, and breathtaking beauty, is the “red thread of biology.”

“For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities – his eternal power and divine nature – have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made.” Romans 1:20

Sources

[1] Campbell, NA: Biologie (S. 15). Heidelberg (Spektrum) 2012

[2] „Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution” Dobzhanski, T: American Biology Teacher 1973; 35:125-129; doi:10.2307/4444260

[3] Die „Evolutionsforschung“ ist hier natürlich eine Ausnahme, wobei sie ja auch eher der Grundlagenforschung als der angewandten Wissenschaft zuzurechnen ist.

[4] Zum Beispiel: „Da es ein Gesetz wie das der Gravitation gibt, kann und wird sich das Universum aus dem Nichts erzeugen.“ Hawking, S: Der große Entwurf. Reinbek (rororo) 2010; S. 177

[5] “Biology is the study of complicated things, that give the appearance of having been designed for a purpose.“ Dawkins, R: The Blind Watchmaker (S. 4). New York (Norton) 1996

[6] Goethe, JW von: Wahlverwandtschaften. Tübingen (Cotta‘sche) 1809; 2. Kapitel, 2. Teil

Image Credits

“Mouse construction site” – Ferdinand Georg

„Blue whale and bat”, “VW and Porsche” – Cornelius vom Stein