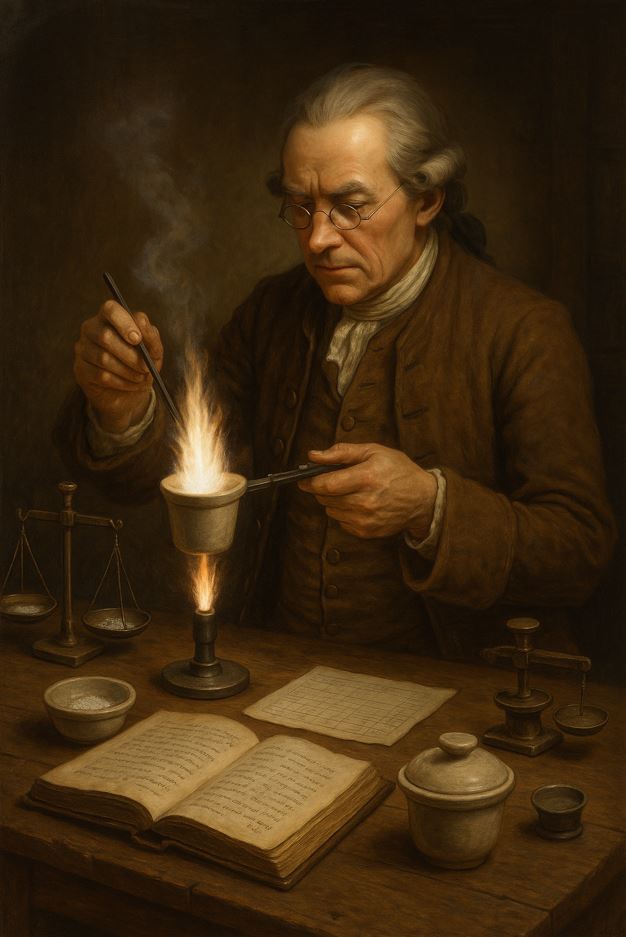

He carefully examines a new ceramic crucible, weighs it precisely, fills it with tin powder, weighs it again, records the values, and places the vessel over the burner’s flame until the contents ignite and burn with a dazzling white light. After cooling it down, he weighs it once more. The calculated differences in mass may vary slightly, but the conclusion is undeniable: the combustion residue, tin(IV) oxide, is heavier than the pure metal before combustion.

This result shouldn’t have been surprising: Frenchman Jean Rey had discovered it 150 years earlier, and Gren’s fellow Berliner Martin Heinrich Klaproth – who had advanced the precision balance into a high-precision analytical tool – had come to the same result just a few weeks earlier. Yet the experimenter is deeply unsettled, because the findings don’t align with his scientific worldview. They contradict the prevailing paradigm and are essentially unthinkable – yet the facts are on the table.

At that time, chemistry was still in its infancy. Combustion processes were explained by the phlogiston theory, a conceptual descendant of the ancient four-element doctrine. According to this theory, a mysterious substance called “phlogiston” is released during combustion. If something is released and escapes, this should be evident through a decrease in mass – something usually observed, except in the case of tin combustion. Today, no one is surprised by this, since we understand the nature of redox reactions. Two molecules of atmospheric oxygen combine with one molecule of tin, without any gaseous products escaping (Sn₂ + 2 O₂ → 2 SnO₂). It’s easy to grasp that the resulting compound must have greater mass.

Dr. Gren employed a bold maneuver to make the facts fit his worldview: he attributed to phlogiston the remarkable property of having (in some cases) “negative weight.” In lengthy debates with his peers, he eventually admitted the flimsiness of this explanation and retracted it. He later proposed an even more adventurous idea: that phlogiston possessed an “original expansive force capable of nullifying or suspending gravity in other substances.” This passed the issue on to physicists, who could only shake their heads at such absurdity. But Prof. Dr. Friedrich Albrecht Carl Gren of Halle was one of the few scientists who eventually realized they had to abandon a cherished theory – and actually did so. He went from being a Saul to a Paul and ended his life as a fierce opponent of the very idea he once represented at the highest level.

It would go too far to delve into the specifics of phlogiston theory, which quickly branched into various interpretations. Many chemical reactions were elegantly explained by theoretical phlogiston constructs. In hindsight, it did contribute to scientific understanding – being the first time that processes like coal or sulfur combustion, iron rusting, and animal respiration were shown to be closely related and based on substance interaction.

However, the role of gases, especially the critical importance of oxygen, was largely overlooked. It is mainly thanks to the French chemist Antoine de Lavoisier that the theory’s many errors could be refuted through well-designed experiments – although the theory’s chaotic variability nearly drove him to despair:

“Sometimes it penetrates vessel walls, sometimes it doesn’t; sometimes it’s contained in light, sometimes in charcoal. It’s used to explain the presence of color, or its absence. In adopting such variability, the theory fits into widely divergent explanatory contexts. Phlogiston is a true Proteus, changing form at every moment.” [1]

In describing this hyper-elastic sponge-theory that explains everything and nothing, immunizes itself against critique through endless add-ons, and still claims the status of a paradigm, one is almost compelled to draw the following comparison:

„Evolution is the phlogiston of our time. It usually proceeds slowly, but sudden leaps can also occur. It explains major transformations or millennia of stability. It accounts for both extreme complexity and elegantly simple solutions. Evolution teaches us how birds learned to fly and how others lost that ability. It makes cheetahs fast and turtles slow; some creatures large, others small; some brightly colored, others dull gray. Evolution depends on chance and lacks direction – yet it appears goal-oriented. Nature is a cruel arena and a place of cooperation. Acquired traits are not inherited – except when they are. Evolution explains good and evil, love and hate, faith and atheism. Like the phlogiston theory, it explains everything – often in vague, unfounded terms.“ [2]

Finnish biochemist Matti Leisola poetically juxtaposes phlogiston and evolutionary theory [3], encouraging further parallels. The phlogiston theory was rooted in the worldview of antiquity and had a long intellectual tradition. Could something supported by the great minds for centuries truly be wrong? // Evolutionary theory, too, draws from ancient developmental ideas. At its core, it reflects the same materialistic mindset that seeks not a Creator, but a creative principle within creation. Today, science is achieving groundbreaking successes – yet when it comes to origins, mainstream research almost exclusively follows this paradigm. Could it still be wrong?

When the phlogiston theory reached its peak, chemistry was still akin to alchemy. New insights into the nature and interactions of elements and matter called for better explanations. // When evolutionary theory broke through, biology was, in the words of evolutionary biologist Ulrich Kutschera, still a “bug-collecting craft” [4]. According to biochemist Michael Behe, the cell was still a “black box” [5]. By the time the incredible complexity and interconnectivity of metabolic processes became known, the evolutionary framework was already firmly in place – though it had (and still has) no answers to many fundamental questions.

In the case of phlogiston theory, there were long “retreat battles,” and some ideas persisted stubbornly. Even the visionary Lavoisier couldn’t fully explain what “heat” was. He established the “caloric theory,” proposing a mysterious, invisible, weightless substance called “calorique” that flowed from hot to cold. This idea was just as wrong as the phlogiston theory and was later discarded. // The founders of evolutionary theory postulated mysterious messengers that supposedly transported adaptation-related information into germ cells for inheritance. Darwin called them “gemmules,” and Ernst Haeckel called them “plastidules.” But just like “phlogiston” and “calorique,” they could not be found or isolated. When inheritance turned out to function very differently, this did not lead to the collapse of evolutionary theory, but rather to its expansion into the “modern synthesis.” Once it became clear that genes determine appearance and that information flows only from gene to trait (not vice versa), mutations – random errors in genes – were declared the source of new information, making chance the creative force. Compared to Gren’s whimsical idea of suspending gravity, the breathtaking notion of turning chance into a creator seems like a child’s prank.

The insight that heat is not tied to “heat particles” but is a form of energy ended the material-focused view of both phlogiston and caloric theory. // The realization that information is not tied to a particular material carrier has the potential to shake the material-based views of evolutionary thinking.

The phlogiston theory was rarely doubted as long as people neither understood the concept of energy (which by nature differs from matter) nor knew how to isolate the gases involved. // The theory of evolution is rarely questioned as long as the concept of information is not fully understood (which by nature cannot arise from random processes), and the source – an intelligent sender – is not acknowledged.

Phlogiston and evolution theories are comparable in many ways. Both have too many adjustable parameters to allow rigorous scientific predictions or falsifiability. However, there is one key difference: the phlogiston theory was eventually refuted and replaced using purely scientific methodology. The missing puzzle pieces were found within chemistry and physics and correctly interpreted through known natural laws. // Refuting evolutionary theory on the grounds of an intelligent source requires a boundary crossing “by faith”: “by faith we understand that the universe was formed at God’s command, so that what is seen was not made out of what was visible.” (Heb 11:3). The idea that the worlds were created by God’s word cannot be proven within the natural realm using science’s limited methods.

The word “phlogiston” comes from phlogizo, the Greek term for “to burn; to set ablaze.” It appears in these verses from the Bible: “Likewise, the tongue is a small part of the body, but it makes great boasts. Consider what a great forest is set on fire by a small spark. The tongue also is a fire, a world of evil among the parts of the body…” (Jas 3:5-6). What is said here about the human tongue and its power resonates with the theme of “hot air.” There are plenty of confused ideologies, conspiracy theories, and fake news circulating. What Christians say should be distinguishable from that: “Let your conversation be always full of grace, seasoned with salt, so that you may know how to answer everyone.” (Col 4:6).

Fußnoten:

[1] Antoine de Lavoisier: Réflexions sur le phlogistique, pour servir de suit à la théorie de la combustion et de la calcination, a. a. O., S. 640 (quoted from A. Schwarz: Das bunte Gewand der Theorie, S. 35)

[2] Matti Leisola: Evolution – Kritik unerwünscht, S. 188

[3] „Theory of evolution” here refers to the biological concept of a common history of descent and development of living beings, as it is represented today in the mainstream of the scientific community (synthetic theory of evolution, STE, modern synthesis).

[4] Ulrich Kutschera: „Wir sind nur eine von Millionen Tierarten“, Focus-interview 31.03.2014

[5] Michael Behe: Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution. 1996

Image Credits:

Wikipedia: Portrait de Monsieur de Lavoisier et sa femme Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze / Jacques-Louis David