The Hebrew word nesher – just like its Greek counterpart aetos – is a term used for large birds of prey and refers collectively to various species of eagles and vultures. Fortunately, additional characteristics are often provided, which allows for more accurate identification.

Eagles are not only extraordinarily strong but also fast and agile despite their size. For many people, they are the most impressive birds of all – the kings of the skies. While other birds may hold records in size, weight, speed, or intelligence, none can match the eagle in terms of strike power and ferocity.

The golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) is one of the largest species and has even been trained in the Asian steppes to hunt fully grown wolves. It has been present year-round in Israel since ancient times and seems to be a fitting candidate for both nesher and aetos, as long as the context does not clearly refer to a vulture. Also living in Israel are the Bonelli’s eagle (Aquila fasciatus) and the Eastern imperial eagle (Aquila heliaca, mostly as a winter guest), both slightly smaller. Less common are the steppe eagle (Aquila nipalensis), short-toed snake eagle (Circaetus gallicus), lesser spotted eagle (Clanga pomarina), and booted eagle (Hieraaetus pennatus).

The traits of a swift and fearless hunter make the eagle a strong symbol of heroism in battle, as in the case of Saul and Jonathan: “they were swifter than eagles” (2 Sam. 1:23), but also of sudden and violent disaster (Job 9:26; Jer 4:13; 48:40; 49:22; Lam 4:19; Hos 8:1; Hab 1:8).

During Israel’s desert journey, God warns His people that He will judge them for disobedience and idolatry: “The LORD will bring a nation against you from far away, from the ends of the earth, like an eagle swooping down, a nation whose language you will not understand” (Deut 28:49). Looking back, we can see that this chapter foretells Israel’s conquests by the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Romans (in that order!). The last were the Romans. They spoke Latin – a foreign, non-Semitic language – and approached not only with the force of an eagle but also bore the eagle as their military standard.

In the visions of the four living creatures representing God’s attributes – as revealed in the Lord Jesus during His time on earth – the eagle symbolizes the Son of God come from heaven in power and majesty (Ezek 1:10; 10:14; Rev 4:7), just as the Gospel of John particularly presents Him.

In Israel, “Eagle” (Nesher) is not known as a personal name, but it is in neighboring cultures. One of King Xerxes’ (Ahasuerus’) seven officials bore the Persian name Karkas (Est 1:10), and the name Aquila also means “eagle.” He was a friend, travel companion, and coworker of the Apostle Paul and bore this Latin name despite being Jewish (Acts 18:2,18,26; Rom 16:3; 1Cor 16:19; 2Tim 4:19).

The image of renewal likely stems from the molting of birds of prey: “He renews your youth like the eagle’s” (Ps 103:5), and: “Those who hope in the LORD will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint” (Isa 40:31).

Some depictions of this process must be classified as legend. For one, eagles do not live to extreme old age, as often claimed – they rarely exceed thirty years, whether in the wild or captivity. Also, it is simply not true that an old eagle sheds all its feathers in a dramatic rejuvenation, only to reemerge youthful with new plumage. Instead, all eagle and vulture species mentioned undergo a gradual, staggered molt.

This fits the spiritual meaning much better. Ideally, we undergo a continual process: “Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day” (2Cor 4:16). That is exactly what we observe in eagles. They spend considerable time cleaning, oiling, arranging, and inspecting their complex plumage – sometimes pulling out damaged feathers. The primary and secondary flight feathers, nearly half a meter long, and the tail feathers must always be in perfect condition. Speed, precision, and safety in flight are at risk if grooming is neglected. With similar care, eagles also maintain their weapons – the sharp beak and strong talons. All this perfectly reflects the deeper meaning of the three Bible verses mentioned. The secret of youthful vitality in Christians lies in continual renewal and refreshment of the inner person through fellowship with God in prayer and Bible reading.

Moses describes God’s care and pedagogical methods as follows: “Like an eagle that stirs up its nest and hovers over its young, that spreads its wings to catch them and carries them aloft. The LORD alone led him” (Deut 32:11). This image is beautiful and has often been vividly elaborated:

“At just the right time, the eagle disturbs its nest and nudges the young out so they learn to fly. Without this prompting, the fledglings would remain comfortably in the nest and continue depending on their parents for food … As the young eagle falls and tries to spread its wings, the mother hovers above. At the right moment, she swoops beneath the falling chick and carries it back to the nest. This repeats until the young eagle learns to fly.”

This touching description seems to match the Bible verse well. In an anonymously published article, someone describes watching a bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) hunt and then draws a parallel to Moses’ words, claiming he “observed something similar.” Sadly, Moses’ description is nothing of the sort. While diving on prey is common among raptors, there is no documented case worldwide of an eagle or vulture (or any bird) ever throwing its young out of the nest to teach them to fly, let alone carrying them back on its back or wings.

Legends ascribe all sorts of feats to eagles: “Then it spreads its strong wings and lets the young rest upon them. Can it carry them? The great eagle would laugh if we could ask him. ‘Of course I can,’ he’d say. ‘I can carry a sheep or a goose for miles to my nest high in the cliffs – why wouldn’t I carry my young?’”

No – eagles cannot carry sheep in their talons, nor their young on their backs or wings. When young eagles or vultures learn to fly, they are nearly the size of their parents! That the parents stay nearby and watch over them is undisputed and confirmed elsewhere: “Like birds hovering overhead, the LORD Almighty will shield Jerusalem” (Isa 31:5). But no known raptor species is remotely capable of carrying its young in flight, though many are physically strong enough to do so. Yet Scripture describes exactly that: “You yourselves have seen … how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself” (Ex 19:4). God’s Word does not spread untruths, even in a nature illustration. However, we should not insert fanciful legends into the Bible.

All known species of raptors have been documented throughout their nesting behavior, and many nests are even equipped with webcams. Such a thing has never been observed. In all ornithological literature, there is only one uncorroborated eyewitness account from 1918, in which a teacher recorded a student’s observation. It was printed as a footnote in the Bulletin of the Smithsonian Institution, a respected scientific journal. Since then, no raptor seems to have attempted this feat again. One would dismiss the entire story as a myth – were it not for the biblical description. There are indeed some waterfowl species, like grebes (Podiceps cristatus), known to carry their young while swimming. The woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) can carry its chicks a short distance in its beak. However, the claim that it can cradle them in its breast feathers remains unproven. According to current ornithological field research, no bird habitually transports its young in flight, though many would physically be capable of doing so. There is no sign in the Bible text that this is a mistranslation or merely symbolic. One could argue that the first half of the verse refers to the eagle, and the second half is transferred to God. Still, God’s care for Israel is far greater and mightier than the picture can express. It remains conceivable that the verse refers to an unknown, now-extinct species.

In the list of birds forbidden for consumption under Jewish dietary law, right after the nesher comes the ozniya (Lev 11:13; Deut 14:12). Its Hebrew name is not very informative. The root oz stands for strength and courage, which fits many large raptors – but that’s all we know. In the Septuagint, the name is translated as haliaetos, clearly referring to the white-tailed sea eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla). Apparently, it was already present in Israel back then. To this day, a few breeding pairs live in the Hula nature reserve. It is even slightly larger and heavier than the golden eagle and is called the “vulture of the north,” as it does not disdain carrion.

Sources:

anonymous: Auslegung zu 5Mo 32,11. Folge mir nach 2021; Heft 01 – Rückseite

anonymous: Wie der Adler (Die gute Saat, FMN), 06.01.2021; https://www.bibelpraxis.de/index.php?article.4377

Bent, AC: Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey. Smithsonian Institution 1937; Bulletin 167, S. 302, siehe: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/32701#page/314/ mode/1up

Edelstam, C: Patterns of Moult in Large Birds of Prey. Annales Zoologici Fennici 1984; 21(3):271-276

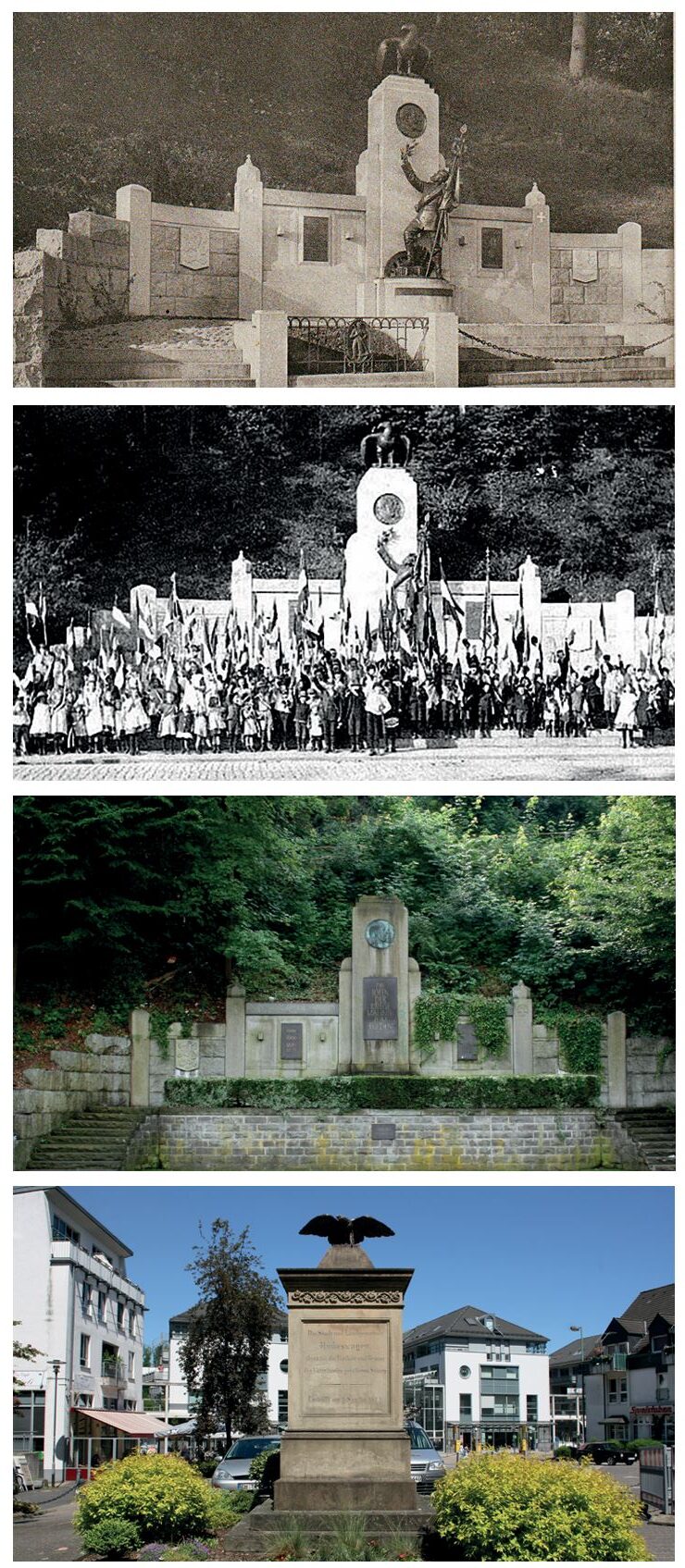

http://genwiki.genealogy.net/Hückeswagen/Kriegerdenkmal_1870/71 (zur Geschichte des Kriegerdenkmals)

Stresemann, V+E: Die Handschwingenmauser der Tagraubvögel. Journal für Ornithologie 1960(101):373-403; doi: 10.1007/ BF01671228

Struwe-Juhl, B; Schmidt, R: Zur Mauser des Großgefieders beim Seeadler (Haliaeetus albicilla). Journal für Ornithologie 2003 (144):418-437; doi: 10.1007/BF02465505

Underberg, A: Absturzängste – und was der Adler uns sagt. Folge mir nach 2012, Heft 5, S. 12-16

Zuberogoitia, I; Zabala, J; Martínez, JE: Moult in Birds of Prey: A Review of current Knowledge. Ardeola 2018; 65(2):183-207; doi: 10.13157/arla.65.2.2018.rp1

Image Credits:

Wikipedia: War Memorial Newly Erected, 1873 / Unknown // War Memorial Today / Frank Vincentz // War Memorial – New Eagle / Frank Vincentz // Church Window, Apostle John with Eagle / Père Igor // Eagle in High Nest / photos-made-by-me.com // White-Tailed Eagle with Carrion / Bohuš Číčel