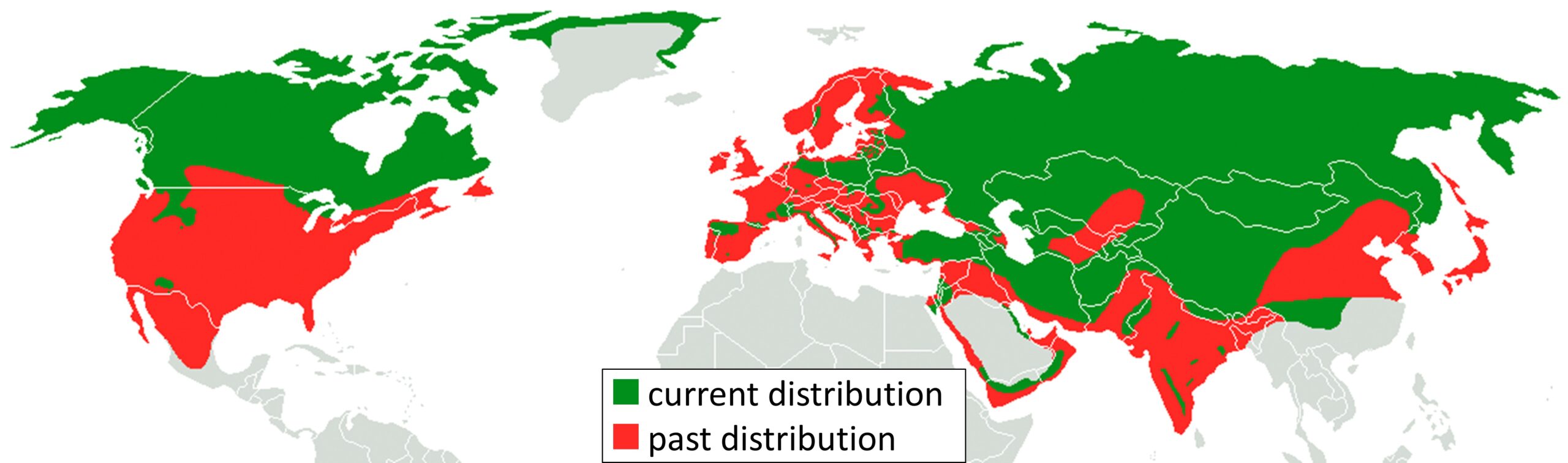

Where there are no lions, the wolf (Canis lupus) often assumes the role of apex predator. Whether in polar regions, forested mountains, or agricultural landscapes: it adapts well across the Northern Hemisphere and was once widespread.

Unfortunately, it frequently clashed with humans. It was relentlessly shot and poisoned until it was eradicated in most areas. In Israel, after the lions were wiped out, the wolf took over their former semi-desert territories and has persisted until today. Recently, it has been making a comeback, provoking very mixed reactions. Environmental activists, mostly urban dwellers in Germany, welcome the trend, while hikers and farmers are often critical. Sheep breeders are appalled.

Although a distinct subspecies was proposed for Middle Eastern wolves – the Arabian wolf (Canis lupus arabs) – due to its visibly different appearance from the gray or Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus), the classification was not accepted. While wolves in the far north can weigh up to 80 kilograms, those in the Middle East rarely exceed 30 kilograms and are much smaller, yet the genetic differences are minor.

The Hebrew word ze’eb (7x) clearly refers to the wolf and even appears as a personal name. One of the Midianite leaders against whom Israel went to war was named Zeeb (Judg 7:25; 8:3; Ps 83:12). He was pursued and killed by warriors from the tribe of Ephraim. The site was then called yekev ze’eb (winepress of Zeeb, or Wolf’s Press) (Judg 7:25).

In Greek, the word for wolf is lykos (5x), derived from leukos meaning “white.” In Greece and Asia Minor, the northern variant was present, with fur mostly in light gray tones. The name of the region Lycaonia in central Anatolia (Acts 14:6,11; modern Turkey) means “land of wolves.”

The wolf is a macrosmatic, a “smelling animal.” After a short patrol, it knows exactly what prey animals are in its territory. The nose is its most important sense organ and vastly outperforms that of humans. It’s often said a wolf can smell “a million times better” – a vivid claim referring to its “technical specs”: the wolf has 280 million olfactory cells that are about 20,000 times more sensitive than the human’s roughly 5 million. The brain area for processing smell is fourteen times larger. Additionally, it can compare scent intensity differences between the right and left nasal passages, enabling “stereo smelling.” Upon finding a scent trail, the wolf can determine its direction simply from minute differences in scent evaporation between two markers. It perceives such tiny traces that it can smell a moose from 2.5 kilometers away with a favorable wind. For us, focused as we are on sight and hearing, it’s hard to imagine the complexity and richness of a “scent world” where far more and subtler smells can be categorized, stored, located, and recognized. This ability is harnessed in many ways with domestic dogs.

Its hearing is also superior to humans’, covering a wider frequency range. Wolves can perceive very high and very low sounds that are inaudible to us. In open landscapes like the Siberian taiga or Middle Eastern semi-deserts, wolves can communicate through their howls over distances of up to 16 kilometers (!).

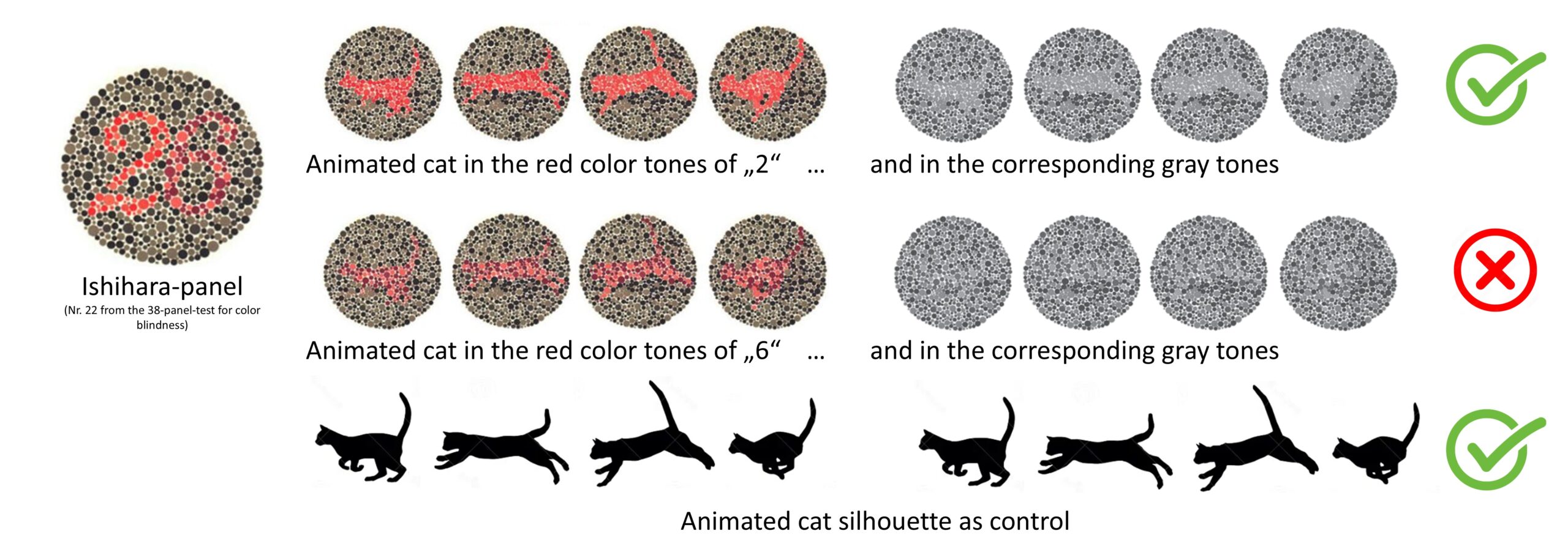

Its vision, however, is less developed, although it excels in detecting movement and has excellent twilight vision. Until recently, it was believed to be completely colorblind, but this proved false – though its color vision is poor. It mainly distinguishes greens and blues and does not perceive red at all.

Its sense of taste is much weaker. Canids are not gourmets – the wolf swallows chunks of prey without savoring them. This made it easy for humans to poison them with baited meat.

Survival is tough for wolves in the Middle East. Where large wild cats dominate, they are pushed out. They’re too slow for swift antelopes and gazelles, can’t sustain themselves on rodents and other small mammals, and are too light to tackle large ungulates. While their northern cousins, often more than twice as heavy, can bring down full-grown moose bulls, the Arabian wolf only dares attack (tame) donkeys and cattle in exceptional cases. Even goats, bravely defending their herd, often chase it off. Thus, discovering a sheep flock is its greatest fortune – perfect prey, if not for the shepherds (and their alert dogs). The predator-prey dynamic between wolf and lamb is so iconic that it’s used symbolically when speaking of future peace: “the wolf shall dwell with the lamb” (Isa 11:6) and “the wolf and the lamb shall feed together” (Isa 65:25).

From ancient times to today, the threat wolves pose to sheep herds has been a bitter reality, and sheep farmers across Europe react with outrage to efforts supporting the wolf’s return, especially where it had been largely eradicated. In the New Testament, the wolf appears in all five verses in its classic role as a terror to the flock. The Lord Jesus warns: “Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves” (Mat 7:15), and Paul later echoes this: “I know that after my departure fierce wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock” (Acts 20:29). It is the destruction they wreak on the flock that reveals these “wolves” – false prophets. Since they disguise themselves with “sheep’s clothing” like piety, eloquence, scholarship, or worldliness, they are readily accepted. This warning can be linked to many heresies and misdirections in Christendom.

This predator image gains profound meaning when the Lord Jesus applies it to Himself. He is the Good Shepherd who lays down His life for the sheep (Joh 10:15) when the wolf comes (and a wolf rarely comes alone). Outwardly, what soon followed seemed exactly like the analogy: Jesus of Nazareth, celebrated as the Messiah – the promised king to shepherd His people Israel – did not reject that role, so power-hungry men (Jewish leaders and Roman authorities) targeted Him. He did not flee but confronted them and was killed, leaving the flock in the hands of these wolves. Yet the Lord revealed in advance that the spiritual reality would be very different: He would take up His life again and save the portion of the flock that recognizes Him as Shepherd and trusts His guidance. His death in the midst of the ravenous wolf pack would, in truth, be a triumph that brings eternal life to His sheep.

Sources:

Hefner, R; Geffen, E: Group size and home range of the Arabian wolf (Canis lupus) in Southern Israel. Journal of Mammalogy 1999; 80(2):611–619; doi: 10.2307/1383305

LIFE WOLFALPS EU: Koordinierte Aktionen zur Verbesserung der Wolf-Mensch-Koexistenz auf Populationsebene in den Alpen. aufgerufen am 21.07.2023: https://www.lifewolfalps.eu

Lord, K: A Comparison of the sensory development of wolves (Canis lupus lupus ) and Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). ethology 2013; 119(2):110-120; doi: 10.1111/eth.12044

Meder, A; Diener-Steinherr, A: Lebendige Wildnis – Tiere der Taiga (Wölfe, S. 7-24). Stuttgart (Das Beste) 1993

Polgár, Z; Kinnunen, M; Újváry, D: A Test of canine olfactory capacity: Comparing various dog breeds and wolves in a natural detection task. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(5):e0154087; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154087

Rinke, A: Der deutsche Wolfs-Wahnsinn. Deutschlandfunk Kultur, 10.06.2015; https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/rueckkehr-der-raubtiere-der-deutsche-wolfs-wahnsinn-100.html

Tooze, ZJ; Harrington, FH; Fentress, JC: Individually distinct vocalizations in timber wolves, Canis lupus. Animal Behaviour 1990; 40(4):723-730; doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80701-8

Image Credits:

Wikipedia: Iberian wolf / Arturo de Frias Marques // historical and current wolf ranges / Mariomassone // Arabian wolf / Ahmad Qarmish12

other licenses: cover image wolf portrait / shutterstock ID_1641141799 / Scott Canning // color vision test for canids / Siniscalchi et al // wolf in sheep’s clothing / shutterstock ID_2192012715 / funstarts33