The term oreb refers to a bird from the genus Corvus, which includes the large ravens and the somewhat smaller crows. The word is derived from arab (“dark”).

Surprisingly, ravens belong to the family of songbirds, even though – unlike other members of this group, which often boast brightly colored plumage – they are as black as young Solomon’s curls: “His face is like the finest gold, his hair is raven black” (Song 5:11). Moreover, they do not chirp or sing, but croak. Their Greek name, korax, is an onomatopoeic representation of this harsh call.

After the common raven (Corvus corax) had nearly become extinct in Israel, it is now making a comeback. It is the most well-known member of its genus. At nearly 70 cm in body length and with a wingspan of up to 130 cm, it is larger than a common buzzard and by far the largest “songbird.” More widespread is the brown-necked raven (Corvus ruficollis), which is slightly smaller but otherwise hard to distinguish from the common raven. The carrion crow (Corvus corone) is smaller still. While it appears entirely black in Central and Western Europe (called the “raven crow”), in Eastern Europe and the Near East it takes on a lighter, gray-black form known as the “hooded crow.” All three species behave and feed in very similar ways. It’s likely they weren’t clearly distinguished in earlier times. The mention of “all kinds of ravens” among the unclean animals (Lev 11:15; Deut 14:14) could indicate that several similar types were grouped together here.

The oreb is the first bird mentioned by name in the Bible: “Forty days later, Noah opened the window he had made in the ark and released a raven. The bird flew back and forth until the ground was dry” (Gen 8:6-7). Noah sent it out from the ark as a scout. The raven flew around and returned to the ark, but not into its interior to Noah. It likely used the roof of the ark as a base and only left when the earth had dried sufficiently and Noah dismantled it (Gen 8:13).

Ravens and carrion crows feed on dead animals and search for food over wide areas. Although they are capable of exploiting a wide range of food sources, they would not be able to raise their young without carrion. God ensures that predators leave part of their prey behind so that scavengers can also feed themselves and their offspring. Ravens and crows are the weakest among the scavengers and usually only get their share once hyenas, jackals, and vultures have had their fill. Thus, they often settle for the carcasses of smaller animals, which they sometimes discover first. The chicks are “nest stayers” and are fed by their parents for a long time. They are constantly hungry and loudly demand food. This audible ruckus has long earned adult birds a bad reputation as “raven parents” who poorly care for their young. Objectively, that is not true. In cultures where ravens are more closely observed, they symbolize parental care. Breeding pairs work extremely hard, and even God uses the raven as a comparison for His own care: “Who provides food for the raven when its young cry out to God and wander about in hunger?” (Job 38:41); “He gives food … to the young ravens when they cry” (Ps 147:9); “Look at the ravens! They don’t plant or harvest or store food in barns, for God feeds them.” God is, in the truest sense, a “raven father.” “And how much more valuable are you than birds!” (Lk 12:24). He uses this unclean and despised bird to show us how much more we mean to Him. If He hears the cry of the young ravens, how much more will He hear the prayers of His redeemed!

Ravens have a high food demand and are able to eat almost anything, including human waste, which has earned them a reputation for being greedy, gluttonous, and thieving. “To steal like a raven” is a common saying. That God used these looters to feed His prophet in the wilderness is therefore a special display of divine power. Elijah receives “meals by raven”: “Leave here, turn eastward and hide in the Kerith Ravine, east of the Jordan. You will drink from the brook, and I have directed the ravens to supply you with food there. So he did what the Lord had told him. He went to the Kerith Ravine, east of the Jordan, and stayed there. The ravens brought him bread and meat in the morning and bread and meat in the evening, and he drank from the brook” (1Kgs 17:3-6).

Unlike vultures, ravens and crows are not afraid to search for food near human settlements, so they are also more likely to scavenge human corpses. Their beaks are multi-purpose tools but not strong enough to tear through tough skin. When they arrive at a fresh carcass, they can usually only access the eyes first. This is indeed what has been observed, and what the proverb collector Agur describes: “The eye that mocks a father and scorns a mother’s instructions will be plucked out by ravens of the valley …” (Prov 30:17).

Their grim reputation as “gallows birds” precedes them, and they are often depicted in association with occult practices, witches, sorcerers, and fortune-tellers. Their appearance is seen as a bad omen – hence the expression “bird of ill omen.” Their black, metallically shimmering feathers and guttural croaking have an eerie quality. Alongside magpies and jays, they are classified as “vermin” in hunters’ terminology. They do not fly elegantly, their hopping on the ground appears awkward, they cannot climb or swim, and they look aged even when young. They also inhabit ruins, as stated of the destroyed cities of Edom: “Ravens will dwell there; He will stretch out over it the measuring line of desolation and the plumb line of emptiness” (Isa 34:11).

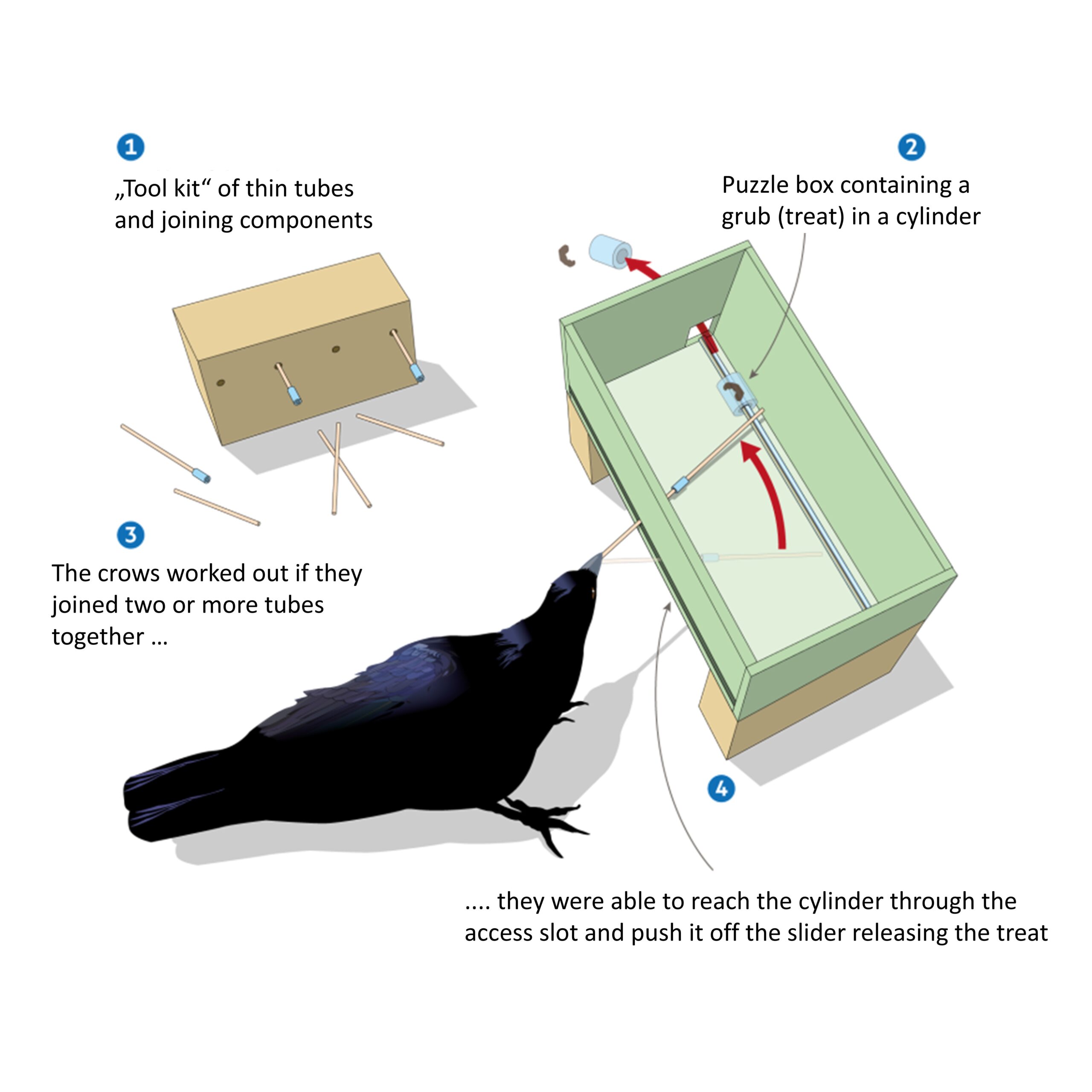

Perhaps ravens were unsettling to people because they repeatedly witnessed their remarkable intelligence. Meat, fish, or dried fruit was often hung on poles to dry. Nets or mesh were meant to protect it from animals, but these “black-market thieves” managed to reach the delicacies with patience and ingenuity. Retrieving a morsel dangling from a string is among their easiest feats. Even more amazing is their apparent ability to understand spatial relationships between objects. In a sensational experiment, it was shown that crows could assemble several elements into a tool to fish out a desired item. Not just in labs, but also in the wild, they have been repeatedly observed using tools creatively.

There are numerous reports of crows laying walnuts on roads, waiting for cars to crush them, and then eating the contents. This behavior was systematically studied by researchers in Japan, who also documented that the birds learn the technique by observing one another. The practice is spreading steadily.

Clear signs of intelligence include the ability to adopt another bird’s perspective – a prerequisite for deceptive strategies – and self-recognition, as observed in mirror tests. Ravens excel in both. Their spatial memory is also phenomenal. In summer, they hide food caches – even in large open areas – and find them again with pinpoint accuracy under winter snow. No wonder they quickly learn to play the card game “Memory,” often beating humans at it.

The rook (Corvus frugilegus) also belongs to the genus Corvus. It appears in Israel only as a winter guest but lives year-round in Greece and Turkey. You won’t find it explicitly mentioned in most German Bibles. Only very precise translations, like the Elberfelder, note in footnotes that it hides behind the term “babbler.” The meaning becomes clearer in this context: “What is this strange bird doing with its pecked-up bits of wisdom?” (Acts 17:18). The Greeks mockingly referred to Paul as a spermologos – a rook.

A rook pecks here and there, taking what others have sown. That’s exactly the accusation made by Epicureans and Stoics on the Areopagus in Athens. As representatives of major philosophical schools, they were confronted with a teaching they couldn’t fit into their system, so they mocked it: “Take an archaic tribal religion, spice it up with some radical ideas like loving enemies and worldwide brotherhood, add a pinch of mysticism like ‘resurrection of the dead,’ stir in a healthy dose of personality cult, and serve it with the looming threat of a terrible judgment.” This sounds much like the objections of today’s naturalist philosophers, who seek to “demystify” the Christian faith. It’s remarkable that access to the gospel comes only by faith – not through mysticism or philosophy, as Paul explained to the Corinthians: “Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles. But to those whom God has called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1Cor 1:22–24).

Sources:

Bayern, AMP von; Danel, S; Auersperg, AMI: Compound tool construction by New Caledonian crows. Scientific Reports 2018; 8:15676; doi:10.1038/s41598-018-33458-z

Cookson, C: ‘Astonishing’ New Caledonian crows make complex tools. Financial Times, Science Report 24.10.2018; https:// www.ft.com/content/5cf8b776-d611-11e8-ab8e-6be0d cf18713

https://www.scinexx.de/news/biowissen/kraehen-spielen-memory-ohne-grosshirnrinde

Nihei, Y; Hicuchi, H: When and where did crows learn to use automobiles as nutcrackers? Tohoku Psychologica Folia 2001; 60:93-97

Reichholf, JH: Rabenschwarze Intelligenz: Was wir von Krähen lernen können. München (Piper Taschenbuch) 2011

Veit, L; Hartmann, K; Nieder, N: Neuronal Correlates of Visu al Working Memory in the Corvid Endbrain. Journal of Neuroscience 2014; 34(23):7778-7786; doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0612-14.2014

Image Credits:

Wikipedia: Tower Ravens / Colin

other licenses: Crows and vultures feeding / AdobeStock_181517813.jpeg / Tatiana // Rooks in the field / shutterstock_58492297.jpg / Vishnevskiy Vasily