Bird migration has fascinated humans since ancient times. Why do competitors, who jealously vie for food and territory all summer, suddenly become companions, gathering harmoniously to embark on a journey together? How do they know when it’s time to depart?

Indeed, as the prophet Jeremiah observes: “Even the stork in the sky knows her appointed seasons, and the dove, the swift, and the thrush observe the time of their migration” (Jer 8:7). In our regions, storks are considered punctual harbingers of spring. But how do they know the way and destination, and how do they find their way back?

For millennia, their enigmatic behavior raised questions. Aristotle believed that storks hid somewhere and hibernated; others thought they transformed into mice in the fall. Around 1700, a rumor spread that migratory birds flew to the moon for sixty days and returned in the spring. The French naturalist Pierre Belon (1517-1564) made his own observations and accurately described bird migration in his work L’histoire de la nature des oyseaux – but few believed him.

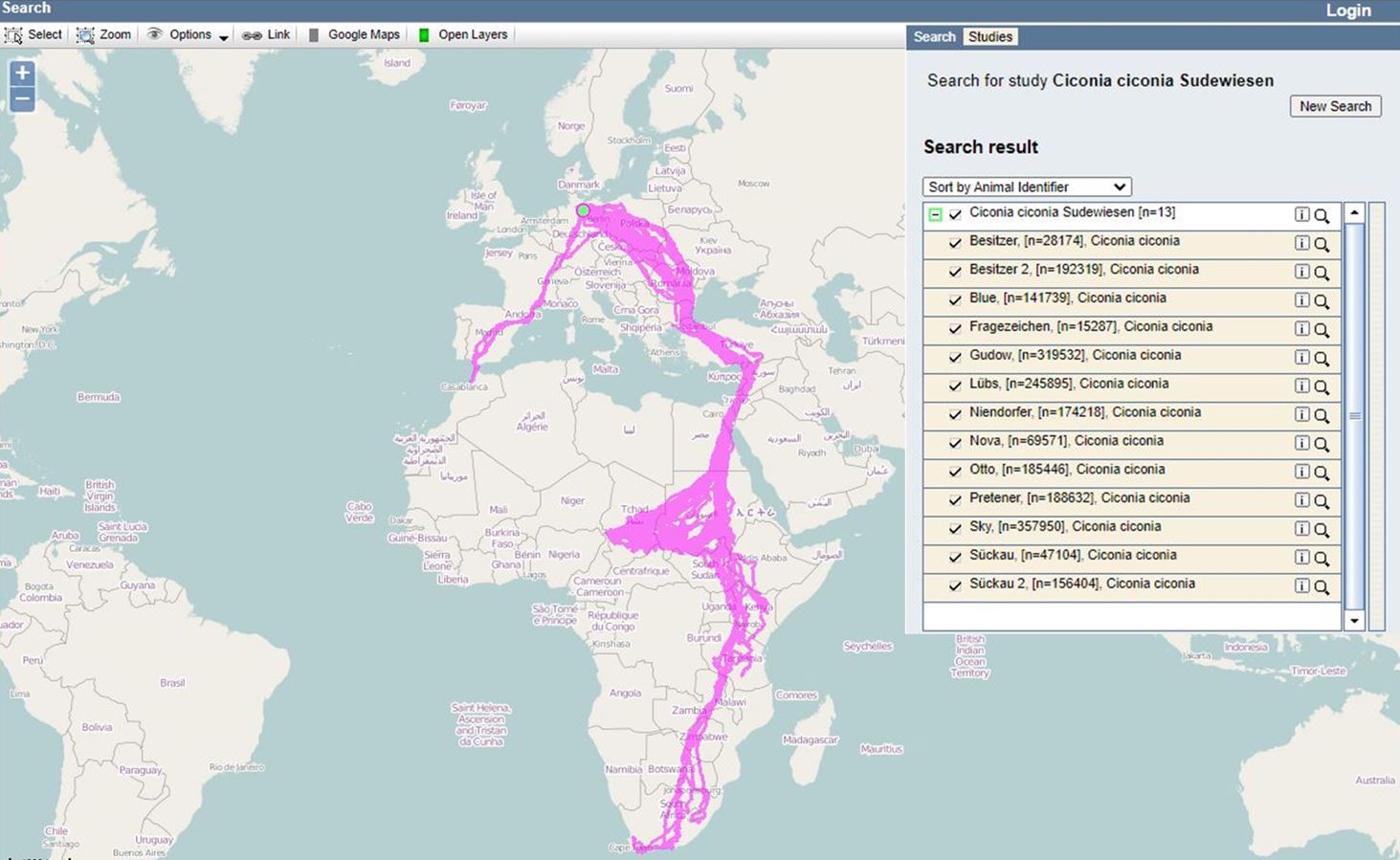

Clear evidence came from the “arrow storks”: animals repeatedly appeared with African hunters’ arrows lodged in their bodies. This proved that storks had indeed been in distant Africa. When birds were fitted with leg rings at the beginning of the 20th century and recaptured and recorded at various locations, the diverse intercontinental travel routes of migratory birds were discovered. Since the beginning of our century, tiny, solar-powered telemetry transmitters with GPS have been used. They can be easily attached to the animal and, depending on the model, provide not only exact position data but also a wealth of other information. Since August 2018, the ICARUS experimental system has been located on the exterior of the ISS space station. Since then, the signals of these wanderers can be transmitted and analyzed even more effectively. This biologging technology allows real-time tracking of birds’ activities. With live cams at nesting, courtship, and feeding sites, they can also be observed around the clock.

Despite all the technical effort and many exciting discoveries, we are still far from having a “transparent bird,” and many questions remain unanswered. The white stork (Ciconia ciconia), which appears in six verses in the Bible as chasida (Lev 11:19; Deut 14:18; Job 39:13; Ps 104:17; Jer 8:7; Zech 5:9), is among the most interesting and well-studied migratory birds.

The presence of storks is unmistakable, as it is accompanied by loud clattering. They clatter to greet and threaten each other, to court, to calm their young, to warn of dangers, and out of sheer joy of life. No wonder these tireless noisemakers, who seem to compensate for their weak voices in this way, are commonly referred to as “clattering storks.”

They are also hard to miss visually: the long beak and even longer legs shine in bright red, and the radiant white plumage on the chest and back contrasts sharply with the black flight feathers. Additionally, they grow to about one meter tall, prefer to stand where they have a good overview, and are therefore easy to observe. Males and females look exactly alike; he is only slightly larger and heavier than she, and it takes a lot of experience to tell them apart.

No one knows exactly how the stork came to be associated with delivering newborns. Besides mystical ideas that see the stork as a sacred bird spending much time in water – a symbol for the beginning of new life and containing the souls of children – there are also more rational approaches. Its massive nest could easily be a cradle. Farmers may have planned the birth of their children for the less busy time in February and March, coinciding with the storks’ return from winter quarters. Perhaps their caring nature and the loving interaction between the pair made them seem like ideal parents.

Statistically, there is indeed a correlation between birth rates and the number of stork breeding pairs in 17 European countries. Thus, the old legend has found its way into many statistics textbooks, illustrating that a constructed mathematical relationship (correlation) is not the same as an actual causal relationship (causality).

Even in their absence, their homes are immediately recognizable: in an elevated location with a 360° panorama, storks build a massive stick nest, which can become even larger than that of native birds of prey and is therefore also called an “aerie.” No European bird builds anything bigger! Nowadays, they almost always use human-made structures in our regions, but where these are entirely absent, they nest on the tops of tall, slender trees – just as described in Psalm 104:17: “The stork has its home in the junipers.” However, since there are generally few suitable places and large branches are needed for the elaborate substructure, bird enthusiasts gladly support the construction project by attaching pallets and shallow wicker baskets as nesting aids on chimneys, masts, or roof gables in preferred breeding areas. On such a solid foundation, the newcomer can immediately start layering and invest more time and energy into the subsequent breeding business. The elaborately designed nesting site, a valuable joint property of the pair, is the “glue in their relationship,” because although they are considered faithful partners and often stay together for life, their true love is for their home.

Typically, an optimally located nest is used again every breeding season for decades. To keep the pair together, it’s important that both adhere precisely to the “schedule,” as the journey to Africa for the “winter vacation” is undertaken individually, sometimes thousands of kilometers apart. Upon return, the male, who arrives first, waits a maximum of one week for the female – before assuming she didn’t make it and seeking a new partner. That sounds harsh, but the risk of standing alone on one leg in the high nest all summer is too great. Fortunately, storks are extremely punctual, as Jeremiah describes in the quoted Bible verse. Considering the weeks-long travel time, it’s astonishing that the timing usually aligns so precisely that the short “grace period” of 5-7 days he allows her is sufficient for a happy reunion.

The partners celebrate their reunion with hours-long “clattering concerts” and begin renovating their nest and repairing winter damage. Additionally, the three or four grown-up young storks from the previous year had made it quite cramped, trampling down the enclosure all around and turning the neatly shaped nursery into a flat “airfield.” To protect the eggs and nestlings of the new clutch from falling out, the nest is raised, and a deep hollow with a surrounding wall is created. Thus, the structure grows a bit taller each spring with a new layer of twigs. An ancient nest becomes a real fortress, a “tower on the tower,” rising meters high, weighing up to two tons, and having already caused some buildings to collapse. It’s often observed that birds of other species, such as starlings, sparrows, little owls, or kestrels, become subtenants in the compact thicket.

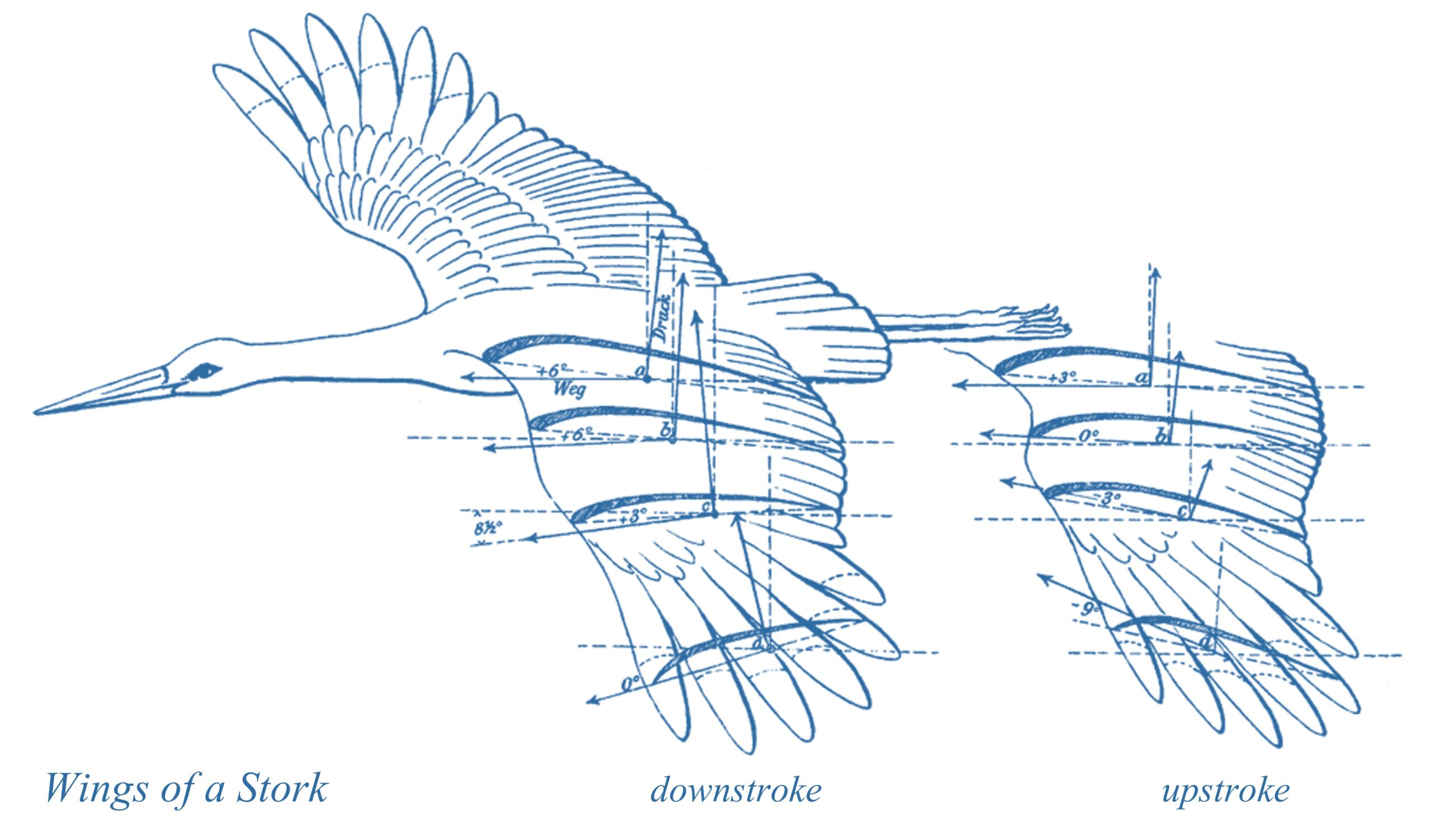

The Bible compares the stork and the ostrich: “The wings of the ostrich flap joyfully – but are they the pinions and plumage of love?” (Job 39:13). At first glance, the contrast seems only to concern their feathers – and indeed: both are large birds with long legs, but while the ostrich has flightless, shaggy wings, the stork’s wings are a marvel of aerodynamic perfection. In Zechariah 5:9, they are admiringly highlighted in a vision: “…whose wings were lifted by the wind. They had wings like those of a stork,” and the German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal considered them the most perfect wing structure in the animal kingdom. They served as a model for his own gliding devices.

The ostrich is later portrayed as neglectful, which further sets it apart from the stork – whose apt Hebrew name chasida means “the kind, gracious, good-hearted, caring one” or simply: “motherly.” The pair’s self-sacrificing parenting is legendary and forms the basis of this bird’s nobility. They take turns foraging and never leave the nest unattended. While the young are small, they are fed with pre-digested, regurgitated food, fairly distributed among them. Later, they are allowed to pick apart the prey themselves – usually fish, amphibians, snakes, small rodents, and insects. The entire family consumes three to five kilograms of food per day.

When the nest is exposed to the blazing sun on hot summer days, the stork parents spread their wings and stand with their backs to the sun to shade their young from early morning until late afternoon – panting in the heat themselves. They also make frequent trips to nearby water, fill their gullets to the brim, and release it in fine streams from their “shower head” over the chicks to cool and hydrate them.

What unfortunately doesn’t fit this family idyll is a selection process known as cainism: when a stork mother feels overwhelmed – if one of her chicks is weak and food is scarce – she may eat it or push it out of the nest. This usually happens with inexperienced first-time mothers and increases the survival chances of the stronger offspring. Here we see the difference between “motherly love” in the animal kingdom – merely a reproductive strategy – and true maternal love, which exists only in humans.

Thanks to their loving all-inclusive care, the chicks grow into impressive juvenile storks within nine weeks, almost reaching their parents’ size. They set off on their journey south once they’ve survived their first flight attempts and completed a brief “basic training.” For these inexperienced newcomers, the first journey is extremely dangerous. After five months, over half of them will be dead; after one year, fewer than a third remain. However, they learn quickly and spend their first three years before reaching sexual maturity in sunny Africa. About one fifth survive this phase and return to their old homeland to breed. Those who make it that far stand a good chance of living up to 35 years. An adult stork has virtually no natural predators left. The parents don’t leave with the fledglings, but stay behind for another one or two weeks and enjoy a brief “time off.” They even engage in courtship play – not with the aim of breeding again, but to strengthen their bond (so it’s not just about the nest) before parting ways for several months.

korken:zieher

The rough travel routes are set: western European storks are “western migrants” that cross the Mediterranean at the Strait of Gibraltar, while eastern European “eastern migrants” cross via the Bosporus through Turkey, the Levant, and Egypt to Africa. The “migration divide” between the two groups runs across Germany. Western and southern German storks migrate west with their French counterparts, while northern and eastern German storks follow the Poles, Balts, and Russians along the eastern route. All are excellent gliders, riding thermal columns up to 2,000 meters in altitude and covering the distance to the next thermal via gliding flight. With this remarkable cruising altitude, they are among the highest-flying birds that can be seen with the naked eye – a fact even referenced by Jeremiah (“the stork in the sky”). Although they cannot glide over large bodies of water and only fly during the day, this method is extremely energy-efficient and allows them to travel long distances.

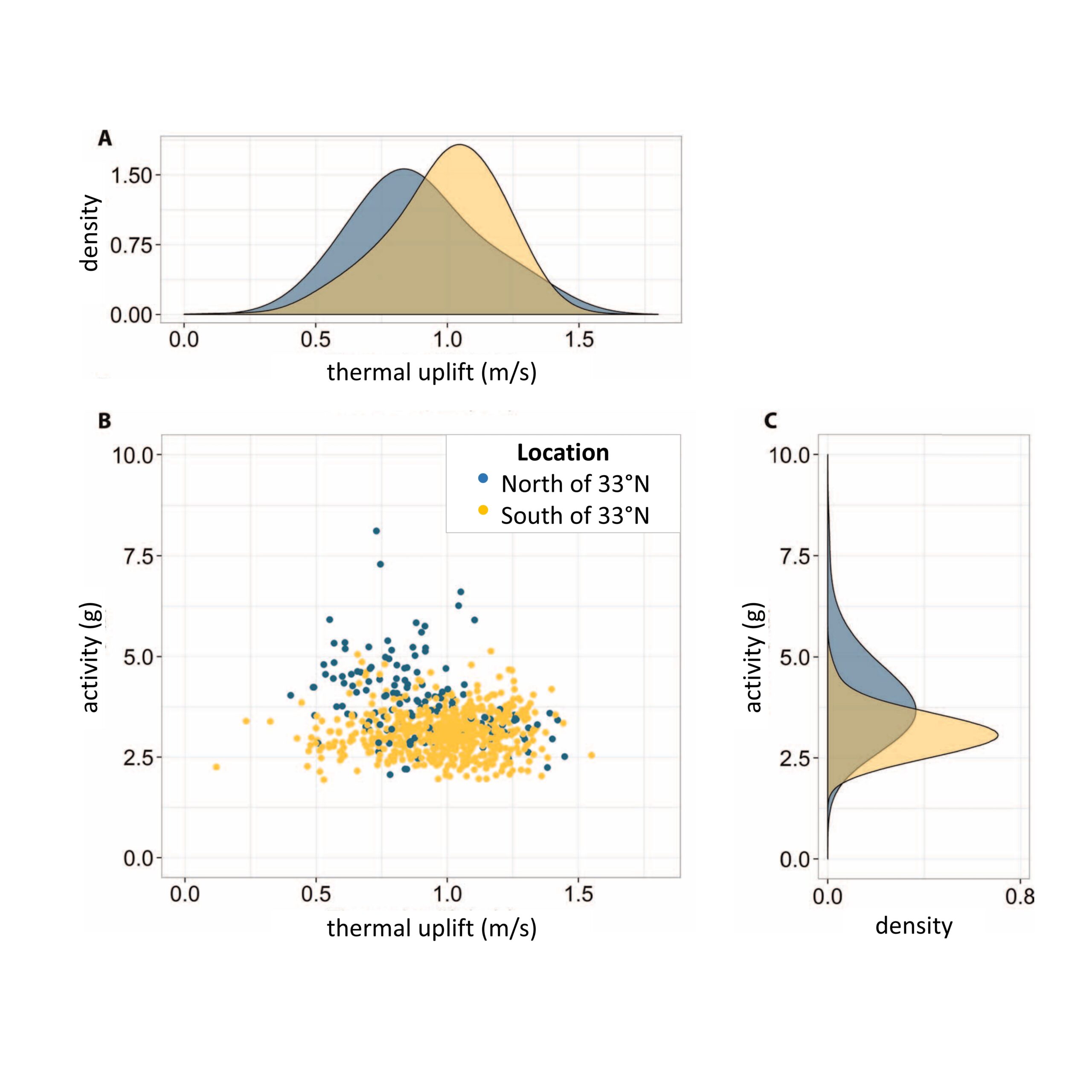

As a recent study has shown, there are significant differences in soaring skills between individual birds – even among siblings from the same clutch. Astonishingly, the animals seem to “know” their strengths and weaknesses and adjust their migration behavior accordingly. The experts fly ahead as “pathfinders” and define the spiral’s position and radius for optimal use of thermals. The less skilled companions can then join the ideal flight path and rise with the current.

Flight skill mastery influences not only group dynamics, but also the choice of wintering grounds. The experts go the distance, while the “flappers” settle for closer refuges and sometimes don’t leave the continent at all, remaining in southern Europe. It is a notable achievement of cutting-edge ornithological field research and modern biologging technology that, using attached acceleration sensors that capture every body movement, one can reliably predict – after just a few minutes of flight analysis – whether a young bird is an efficient glider soon to lead a group toward distant South Africa, or whether effortless soaring just isn’t his thing, and he’s more comfortable staying in southern Spain.

There’s much more to say about the stork, but we’ll end this overview with an invitation to take it as a role model: In an astonishing way, Master Adebar (from Old German Odobero = “bringer of fortune”) is aware of his strengths and weaknesses, contributes accordingly to the group, and sets realistic goals. We could all take a page from that book: “Each of you should use whatever gift you have received to serve others, as faithful stewards of God’s grace in its various forms” (1Pet 4:10).

Sources:

Curry, A: The internet of animals that could help to save vanishing wildlife. Nature 2018; 562:322-326; doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-07036-2

Flack, A; Fiedler, W; Blas, J: Costs of migratory decisions: A comparison across eight white stork populations. Science Advances; 2016; 2:e1500931

The story of Prinzesschen: https://www.storchenhof-loburg.de/prinzesschen-63.html

Matthews, R: Der Storch bringt die Babys zur Welt (p = 0.008). Stochastik in der Schule 2001; 21(2):21-23 https://www.stochastik-in-der-schule.de/

Vergara, P; Gordo, O; Aguirre, JI: Nest Size, Nest Building Behaviour and Breeding Success in a Species with Nest Reuse: The White Stork Ciconia ciconia. Annales Zoologici Fennici Jun 2010; 47(3):184-194; doi: 10.5735/086.047.0303

Image Credits:

Wikipedia: Arrow stork / Zoologische Sammlung der Universität Rostock // Storks clattering / J. Patrick Fischer // Stork nest on bell tower / Emilio Posada // Stork nest on rooftop / MES // Stork wing sketch by Lilienthal / Michael

Other licenses: Flying stork / AdobeStock_182263285.jpeg / Joachim Neumann // Mating storks / AdobeStock_59650587.jpeg / Ana Gram // Nest-building storks / AdobeStock_61289210.jpeg / Ivan Kmit // Memorial for stork “Prinzesschen” / D59Y1X.jpg / dpa