In the Bible, the terms namer / nemar and “pardalis” refer to either the leopard (Panthera pardus) or the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus).

Both species were common in the Middle East and, until a few centuries ago, were barely distinguished. The cheetah was also called a “hunting leopard,” and both together were referred to as “pardel.” Therefore, it is quite possible that one or the other is meant in various biblical passages. In terms of danger and ferocity, the leopard is the more suitable candidate; in terms of extreme speed, the cheetah fits better.

The Hebrew word namer (Song 4:8; Isa 11:6; Jer 5:6; 13:23; Hos 13:7; Hab 1:8) and its Aramaic counterpart nemar (Dan 7:6) derive from a root meaning “to drip/permeate” (as in filtering or dyeing) – likely a reference to the spotted fur. It also appears in place names like Beth-Nimrah (Num 32:36; Jos 13:27) – “house of the leopardess” – and its short form Nimrah (Num 32:3). At the “waters of Nimrim” (Isa 15:6; Jer 48:34), the root likely refers not to the predator, but to the “dripping” meaning. In modern Hebrew, nemar denotes the leopard, while the cheetah is referred to by the Indian term “cheetah” (as in English).

The Greek pardalis (Rev 13:2) is a short form of pardaleon (as in the LXX of Song 4:8) and means “panther-lion.” Later, the form leopardos became established, from which the Latin (and German) term “leopard” is derived.

Regarding the leopard, the habitats of the Arabian leopard (Panthera pardus nimr, South Israel), Sinai leopard (P. p. jarvisi, Sinai Peninsula), and Persian leopard (P. p. saxicolor, northeast) overlap in Israel. The leopard is the most widespread and adaptable big cat, a skilled climber that hunts successfully in forests, mountains, and open landscapes. Thus, it likely lived in Lebanon’s mountain range – “the mountains of leopards” (Song 4:8). The Asiatic cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) has been described, but due to minimal variation, its classification remains questionable.

Most German Bible translations alternate between “Leopard” and “Panther,” which is misleading. Today, “Panther” refers only to the black form of the leopard (virtually never seen in the Middle East), and older terms like “Pardel” (AElb, Menge) or “Parder” (AM) are no longer used. Only the Revised Elberfelder (ÜElb) and Hoffnung für alle (Hfa) consistently translate with “Leopard.” The English New Living Translation chooses “cheetah” in a verse about speed: “Their horses are swifter than cheetahs” (Hab 1:8) – rightly so, as we will see.

Both leopard and cheetah are marked by their strikingly spotted coats. This distinction is helpful: cheetahs have “dots,” while leopards display beautiful rosettes. The Hebrew word chabarbura, used only in this context, means “formation.”

The Bible refers to this feature: “Can a Cushite change his skin or a leopard his spots? Then you also can do good who are accustomed to doing evil” (Jer 13:23). Two unchangeable natural appearances serve here as a spiritual metaphor. Both arise from a high production of dark pigment (melanin). The spot pattern is genetically fixed and cannot be hidden. Even the black panther, a melanistic leopard, is not an exception – under bright light, the hidden spots are still visible.

What Jeremiah said applies not only to Israel but to all people: we cannot change our nature, being “accustomed to do evil.” The Hebrew word limmud, from lamad (to teach), implies being trained or taught – in Isaiah 8:16 it is translated “disciple.” By nature, every person is a disciple of sin and incapable of doing good on their own.

But a prophetic statement says: “The Lord GOD has given me the tongue of those who are taught [limmud], that I may know how to sustain with a word him who is weary. Morning by morning he awakens my ear to hear as those who are taught [limmud]” (Isa 50:4). Through the death of Jesus Christ, what is naturally impossible becomes possible. Believers can say with Paul: “Our old self was crucified with Him so that the body of sin might be rendered powerless, that we should no longer be slaves to sin” (Rom 6:6). Thus, we truly shed our old skin and “put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator” (Col 3:9.10).

Cheetahs tend to avoid humans. Except for wounded individuals defending themselves, there are few known cases of cheetahs attacking humans. Therefore, when God uses a wild animal as an image of judgment, it is likely the leopard: “A lion from the forest will attack them, a wolf from the desert will ravage them, a leopard will watch their cities: everyone who goes out will be torn to pieces” (Jer 5:6). While symbolic of judgment by foreign nations, this also reflects the real threat from such predators. Leopards specialize in hiding in trees and ambushing their prey with powerful leaps. With a weight of up to 90 kg, immense jumping ability, and sharp claws, a leopard attacking from behind leaves little chance for survival. The awareness of such an unseen predator lurking nearby must be terrifying. God describes Himself as this pursuer in judgment: “I will lurk like a leopard by the path” (Hos 13:7).

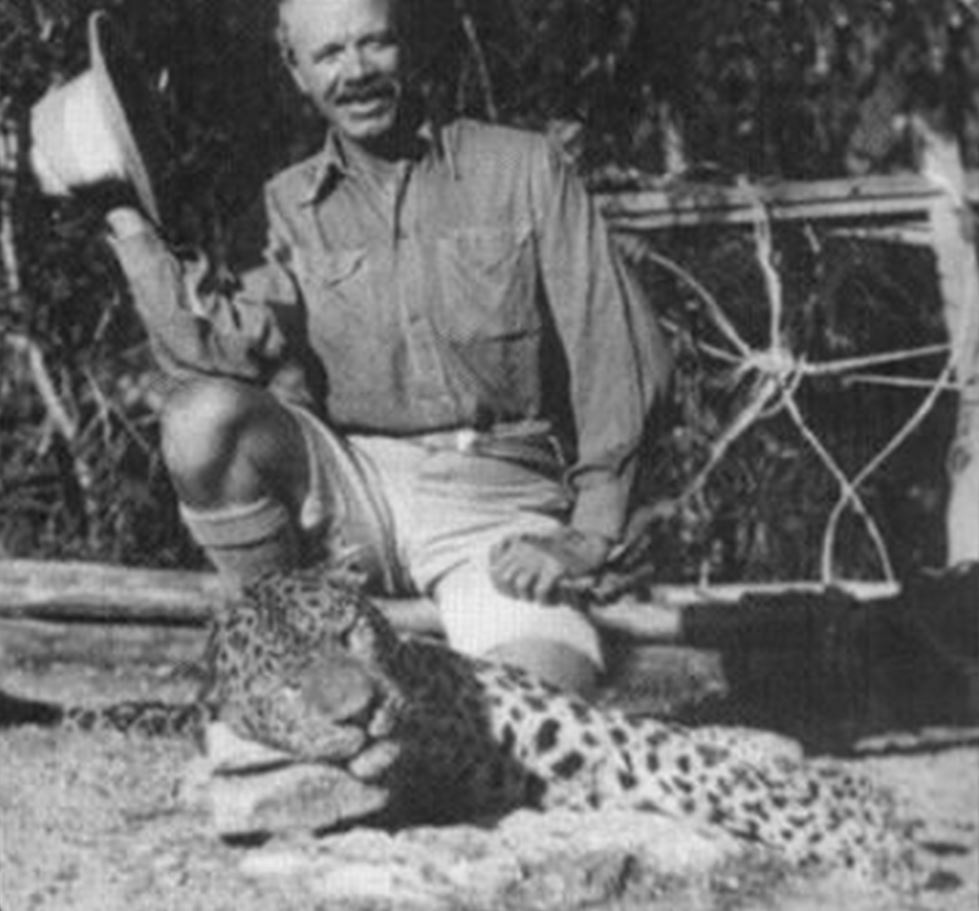

Despite their natural fear of humans, leopards quickly become “repeat offenders” once they discover how easily they can overpower them. “The Man-eating Leopard of Rudraprayag” is the title of a book by big-game hunter Jim Corbett, who killed a leopard that had repeatedly attacked and killed people over several years – allegedly 125 victims. Fear gripped the region until the animal was finally brought down.

In the future peaceful kingdom described in the Bible, such threats will vanish: “The leopard will lie down with the young goat […] and a little child will lead them” (Isa 11:6).

There is no better symbol of speed than the cheetah – the fastest land animal. Its entire anatomy is designed for high-speed hunting, and its genetics are so uniform that all living cheetahs are nearly genetically identical – similar to identical twins, a rare trait among higher animals.

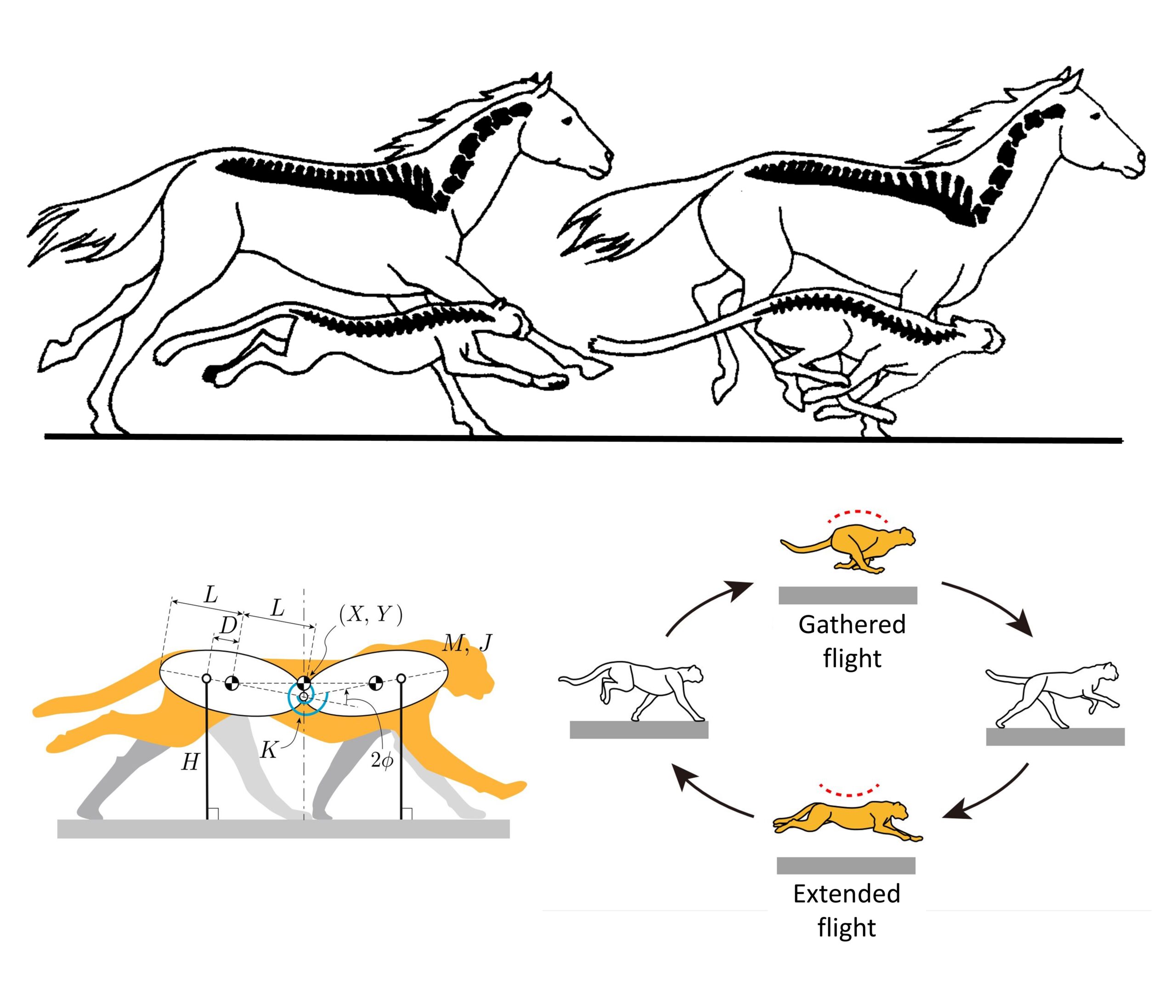

Heart, lungs, bronchi, and nostrils are enlarged. Muscle fibers are optimized for rapid contraction. The adrenal glands produce high levels of adrenaline. A strong 60-cm tail stabilizes its run, and a highly flexible spine acts like a spring, enabling powerful motion. This, along with a lean body, short claws, and firm footpads, provides excellent traction.

Unlike most other big cats, the cheetah is diurnal and prefers the morning hours for hunting, before the sun reaches full strength. His method works best in the open savanna, where there are no obstacles to slow him down. From an elevated vantage point, he surveys the terrain, selects a group of grazing antelope, and then proceeds with surprising deliberation: first, he stalks carefully – a process that can take up to two hours. In doing so, he moves much more inconspicuously than a lion and can often get within 30 meters of his prey while staying hidden in tall grass.

What follows is completely unexpected: instead of leaping up like a lion and rushing forward, the cheetah simply emerges from the grass and jogs casually toward the group. He “presents” himself to the antelopes, which immediately flee. What does this mean? Why would he waste valuable time and distance? This is still somewhat mysterious, but it’s believed that the cheetah uses this phase to carefully assess the prey: which animal reacts how quickly, which one panics, which one remains in control? If one is clearly slower or less coordinated, he selects it and focuses entirely on that target.

As he drives the herd forward, individual animals repeatedly perform high stotting leaps during full gallop – with arched backs and stiff legs, straight up into the air. This “stotting” or “pronking” costs them a lot of energy – shouldn’t they rather just run? Yes, they should. Studies have shown that the purpose of this acrobatics is to display fitness and deter the predator from an unpromising chase. It works with wild dogs and hyenas – but not with cheetahs. Once a cheetah has chosen a victim, he cannot be distracted by all that jumping.

Now he accelerates to the maximum speed unmatched by any land animal. High-speed footage now shows this sprint in all its glory. There are two “flight phases”: one where the body is fully stretched, soaring up to eight meters in one leap, and one where it is completely curled. During both, there is no ground contact. Each of his paws touches the ground about three times per second. What looks like a series of elegant ballet leaps in slow motion is actually a frenzied drumbeat of twitching fore- and hindlegs. His body heats to 40°C, his pulse is at the limit, and with 150 breaths per minute – even with enlarged airways – he cannot pump more oxygen into his system. After a few seconds of sprinting, he slows down. But that’s enough. The goal of this crazy rush is primarily to unnerve the prey. For flight animals like Thomson’s gazelles or impalas – dependent entirely on speed and otherwise defenseless – it’s a traumatic situation to have a faster predator on their tail. They panic and veer off. That’s what the cheetah was waiting for, and why he slightly reduced his pace. Just as important as his top speed is his incredible agility. At full speed, he changes direction and gives the impression that he already knew whether his target would dodge right or left. His turning radius is tighter than any prey animal. Every sidestep the prey takes gives him an advantage, and the hunt ends quickly. With a swipe of his forepaw, he unbalances the exhausted antelope and finishes the hunt by biting her throat, suffocating her. With this strategy, he may be the most successful predator in terms of attack-to-kill ratio.

katzen:klauen

Where someone is particularly successful, nature usually has a mechanism to restore balance. So the cheetah’s story must be told completely – he pays a high price for his performance. After a kill, he is so breathless that he collapses, needing up to twenty minutes to recover before he can eat. During this time, he is extremely vulnerable. Lions, hyenas, leopards, wild dogs, and even jackals all envy his success and try to steal the kill. Often vultures show them the way. In some territories, he loses over half of his kills without ever getting a bite. His lightweight build means he would lose a fight – and in encounters with lions or hyenas, he might not just lose his meal, but his life. Sometimes that happens – if he’s too exhausted to escape. It’s a signature trait of the cheetah: quick and successful hunts – but often followed by loss, sometimes even death.

As mentioned earlier, cheetahs and leopards were hardly distinguished in the past. In three biblical passages, rapidly unfolding events are compared — and the “cheetah” fits better.

In Daniel’s vision of four beasts rising from the sea – a preview of successive empires – the Greek empire is described: “After that, I looked, and there before me was another beast, one that looked like a leopard. And on its back it had four wings like those of a bird. This beast had four heads, and it was given authority to rule” (Dan 7:6). No other conquest campaign in history was faster or more militarily successful than Alexander the Great’s campaign (356-323 BC). In just a decade, he conquered territory from Greece to the Himalayas and from the Indus to southern Egypt. But he did not enjoy it long – dying far from home. His empire was divided among Antigonus, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Seleucus. Their mutual rivalry quickly eroded their power.

650 years later, the Apostle John describes a new beast rising from the sea: “The beast I saw resembled a leopard, but had feet like those of a bear and a mouth like that of a lion. The dragon gave the beast his power and his throne and great authority” (Rev 13:2). This empire will rapidly take control over the world – but only for a short time: 42 months (Rev 13:5).

The prophet Habakkuk describes Babylon’s fast-approaching armies: “Their horses are swifter than leopards, fiercer than evening wolves. Their horsemen gallop headlong; their horsemen come from afar; they fly like an eagle swooping to devour” (Hab 1:8). Most trained horses are faster than leopards – but if cheetahs are meant, the metaphor is even stronger. This fits the swift rise of Nebuchadnezzar’s Mesopotamian coalition after Assyria’s fall. With a duration of just 70 years, Babylon was also short-lived.

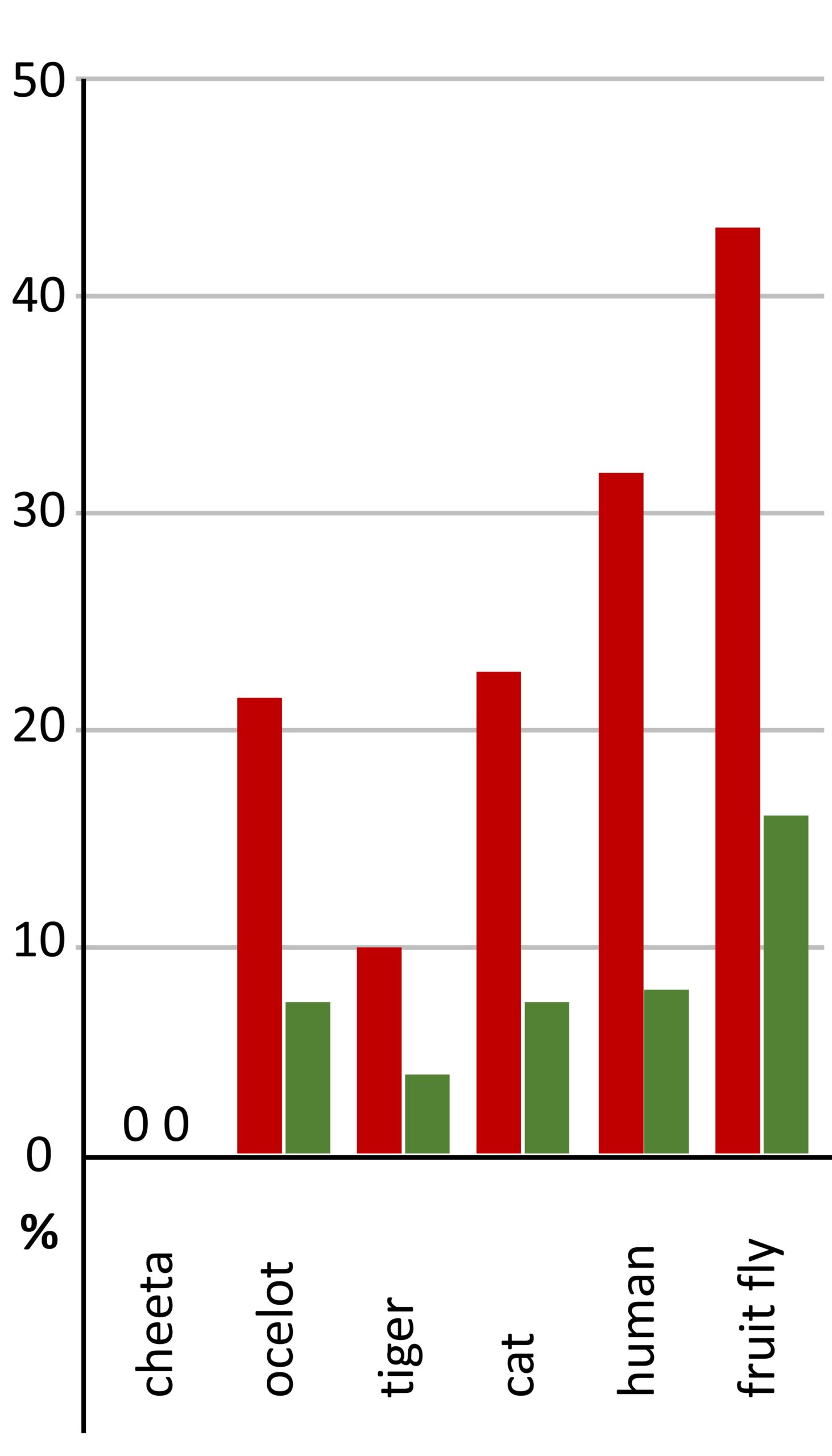

What exactly is the cheetah’s top speed? Isn’t it frustrating that every source says something different? 120, 114, 113, 104, 98, and 93 km/h – all measured in the most cited studies. So many factors influence speed that knowing the exact number is less important. Weight, fitness, wind, terrain, and temperature all matter.

Still, no land animal is faster. Thomson’s gazelles have reached 90 km/h, so the cheetah must give it his all in pursuit.

Sources:

Bartwal, DM; Puram, B; Garhwal, NT: Environmental Consciousness in Jim Corbett’s “The Man-Eating Leopard of Rudraprayag”. The Indian Review of World Literature in English 2017, 13(2):1-7; https://worldlitonline.net/contents_jul_2017/July%2017_article_1.pdf

Caro, TM: The functions of stotting in Thomson’s gazelles: some tests of the predictions. Animal Behaviour 1986; 34(3):663-684; doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(86)80052-5

Corbett, J: Leoparden, die Mörder im Dschungel. Zürich, CH (Orell-Füssli) 1950; deutsche Übersetzung des englischen Originals: The Man-eating Leopard of Rudraprayag. New York (Oxford University Press) 1948

Eizirik,E; Yuhki, N; Johnson, WE: Molecular genetics and evolution of melanism in the cat family. Current Biology 2003; 13:448-453; https://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(03)00128-3.pdf

FitzGibbon, CD; Fanshawe, JH: Stotting in Thomson’s gazelles: an honest signal of condition. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 1988; 23:69–74

Hayward, MW; Hofmeyr, M; O’Brien, J: Prey preferences of the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) (Felidae: Carnivora): morphological limitations or the need to capture rapidly consumable prey before kleptoparasites arrive? Journal of Zoology 2006; 270(4):615-627; doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00184.x

Hetem, RS; Mitchell, D; Witt, BA: Cheetah do not abandon hunts because they overheat. Biology Letters 2013; 9(5); doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0472

Hilborn, A; Pettorelli, N; Orme, CDL: Stalk and chase: how hunt stages affect hunting success in Serengeti cheetah. Animal Behaviour 2012; 84(3):701-706; doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.06.027

Hunter, JS; Durant, SM; Caro, TM: To flee or not to flee: predator avoidance by cheetahs at kills. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2007; 61:1033-1042; doi: 10.1007/s00265-006-0336-4

Kamimura, T; Aoi, S; Higurashi, Y: Dynamical determinants enabling two different types of flight in cheetah gallop to enhance speed through spine movement. Scientific Reports 2021; 11:9631; doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88879-0

Kaplan, M: Speed test for wild cheetahs. Nature 2013; 498:150; doi: 10.1038/498150a

Meder, A; Blank, S; Dank, U: Lebendige Wildnis – Tiere der Wüsten und Halbwüsten (Geparde, S. 7-24). Stuttgart (Das Beste) 1993

Mills, MGL; Broomhall, LS; Toit, JT: Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus feeding ecology in the Kruger National Park and a comparison across African savanna habitats: is the cheetah only a successful hunter on open grassland plains? Wildlife Biology 2004; 10:177-186; doi: 10.2981/wlb.2004.024

Podbregar, N: Gepard: Geschwindigkeit ist nicht alles. wissenschaft.de, 4. September 2013; https://www.wissenschaft.de/erde-umwelt/gepard-geschwindigkeit-ist-nicht-alles

Rani, P; Kumar, N: Foregrounding the Animal Stance: A Critical Study of Man-Eating Leopard of Rudraprayag. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities 2017; 9(3):151-160; doi: 10.21659/rupkatha.v9n3.16

Scantlebury, DM; Millsrory, MGL; Wilson, P: Flexible energetics of cheetah hunting strategies provide resistance against kleptoparasitism. Science 2014; 346(6205):79-81; doi: 10.1126/science.1256424

Sharp, NCC: Timed running speed of a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). Journal of Zoology 1997; 241:493-494; doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb04840.x

Wilson, JW; Mills, MGL; Wilson, RP: Cheetahs, Acinonyx jubatus, balance turncapacity with pace when chasing prey. Biology Letters 2013; 9; doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0620

Wilson, A; Lowe, J; Roskilly, K: Locomotion dynamics of hunting in wild cheetahs. Nature 2013; 498:185–189; doi: 10.1038/nature12295

Image Credits:

Wikipedia: Leopard–Lion hybrids / TRJN // Big-game hunter Jim Corbett / Shiva // Springbok in stotting jump / Charles Jorgensen

other licenses: Leopard Portrait / ID_635825570 / VarnaK // Melanism, black panther / ID_672423601 / jeep2499 // Coat pattern comparison (cheetah) / ID_719157937 / Volodymyr Burdiak // Coat pattern comparison (leopard) / ID_1183492993 / TigerStocks // Cheetah direction change / ID_484873690 / JonathanC Photography // Cheetah with prey / ID_184058318 / Maggy Meyer // Cheetah sprint mechanics / Kamimura et al