It is said of Panthera leo: »A lion, which is mighty among beasts And does not turn away from any« (Prov 30:30).

The fearsome big cat was once widespread across North Africa, Southeastern Europe, the Levant, and all of the Near East to India – and fossil records even show its presence in the Americas. However, due to intensive hunting, many lion populations in the Roman Empire were already extinct by late antiquity. In Israel, lions survived until the Middle Ages, and in North Africa even until the 20th century. Today, wild lions are only found south of the Sahara.

The lion is mentioned in 125 Bible verses. Though the title “King of Beasts” is reserved for the Leviathan (Job 41:26), who plays in a different league altogether, the lion is still the most frequently used symbol for majesty, power, and force. Its significance is shown in the many different Hebrew names used for it.

Most common is the Hebrew ari and the Aramaic arie (used ~80 times), referring both to the male lion and the species in general. Derived from the verb ara – “to tear apart,” this root also appears in terms like lion-hearted (2Sam 17:10), lion-faced (1Chr 12:9), lion teeth (Joel 1:6), and lion’s den (Dan 6:8.13.17.20.25). The form Ariel – “Lion of God” – is used for famous warriors (2Sam 23:20; 1Chr 11:22) and for the heroic city of Jerusalem (Isa 29:1-2:7). Some men were named Ari or Arieh (2Kgs 15:25) and Ariel (Ez 8:16) – still popular first names today (for boys and girls). Other lion-related names include Aridata – “strong as a lion” (Est 9:8), Arioch – “lion-like” (Gen 14:1.9; Dan 2:14-25), and Arisai – “lion-banner” (Est 9:9).

The lioness is called labi (14x), unusually in the masculine form, which may suggest her equally heroic nature. She’s usually mentioned alongside the male. The plural form appears in the place name Beth-Lebaot (Jos 15:32; 19:6) – “House of the Lionesses.” I wonder if you would like to live there?

Possibly, even the Greek leon, used in the New Testament (9x), is derived from the same Semitic roots. The popularity of names like Leo, Leon, Leonie, Leola, Leonardo, Leonidas, and Lionel confirms the ongoing trend of lion-inspired names. Adolescent lions are called kefir (31x), while their female counterpart appears only in the place name Kephira (Jos 9:17; 18:26; Ez 2:25; Neh 7:29) – “young lioness.” Lion cubs are gur or gor (7x). The heroic lion is also described poetically as lajisch (Job 4:11; Prov 30:30; Isa 30:6), derived from lusch – “to knead, to oppress.” Additional poetic descriptors include schachal – “roarer” (7x), okel – “devourer,” and az – “strong one” (Judg 14:14).

“What is stronger than a lion?” (Judg 14:18) – Samson’s wedding guests in Philistine Timnah considered the answer obvious in his riddle. Lions symbolize violent, explosive power, as shown by the comparison: “Saul and Jonathan… were stronger than lions” (2Sam 1:23).

Although all large animals are “strong,” only recently have scientific methods confirmed that lions and other big cats possess specialized muscle fibers (type II-x), physiologically different from other species and extremely efficient. Lions (along with tigers) rank highest in energy output among predators.

As apex predators, lions dominate savanna food chains. They prefer prey that outweighs them—sometimes more than double their weight—and can bring them down. Compared to zebras, which are larger, faster, and more enduring, lions have 20% more muscular output, 37% better acceleration, and 72% greater braking power.

All of this would be of no use to the lion if the zebra could simply run away. That’s why, when hunting alone, the first few seconds are crucial. Crouched low to the ground and using every bit of cover, the lion tries to get as close as possible to its prey without being detected. This ambush tactic is vividly described in the Bible: “He crouches, he lies down like a lion” (Gen 49:9; Num 24:9); “He lurks in hiding like a lion in dense thickets” (Ps 10:9); “I will be like a lion to them, like a leopard I will lie in wait by the path” (Hos 13:7); “Can you hunt the prey for the lioness or satisfy the appetite of the young lions when they crouch in their dens or lie in wait in the thicket?” (Job 38:39-40).

The real highlight is the explosive launch: “like a young lion leaping from the thickets of Bashan” (Deut 33:22). The lion begins the hunt with a powerful leap – up to seven meters long – propelling itself from its hiding place at 85 kilometers per hour. This impulse transitions into a sprint as it charges at the herd at 60 kilometers per hour. The zebras react almost instantly and scatter, but they can’t match the lion’s initial acceleration, allowing it to quickly close the gap. However, if the terrain allows them to reach full speed without detours, they soon outrun the lion, which is why it mainly catches old or sick animals.

In wildlife documentaries, lions are usually shown hunting hoofed animals. Zebras, wildebeests, African buffaloes, antelopes, gazelles, and warthogs are often their favorite prey, sharing the same habitat. After a kill, jackals and vultures sometimes attempt to steal scraps—but they would be wise to wait until the lions are full, lest they become dessert themselves. The same applies to hyenas, which may challenge lions in packs.

Lions interpret their role as carnivores quite generously: they may be seen fishing in shallow lagoons and won’t pass up crawling insects either. They’re highly intolerant of food competitors. Leopards, cheetahs, and wild dogs are advised to avoid lion prides altogether. Birds, rabbits, mice, and other rodents aren’t worth the chase – unless the opportunity is favorable. Only very inexperienced lions mess with porcupines – usually to their regret.

Because lions are highly adaptable in their hunting behavior, it’s difficult to describe a standard hunting scheme. They mostly hunt at night, but if the terrain offers enough cover or their prey is active during the day, lions will adjust accordingly. While hoofed animals remain their staple diet, some prides specialize in hunting ostriches, giraffes, hippos, crocodiles, elephants, and rhinos (though only juveniles of the latter two). Along Namibia’s Atlantic coast, lions have even been observed ambushing sunbathing brown fur seal.

Their hunting tactics also vary: in denser terrain with more prey, lions tend to hunt alone. In open spaces, they usually hunt in groups. When food is scarce, even males join, though they usually do not participate in group hunts. During these coordinated hunts, prides showcase impressive teamwork: drivers circle and direct the herd, while ambushers wait at key points, quickly choosing and singling out a target. Larger prey such as zebras, wildebeests, and buffalo are killed by a throat clamp that blocks their windpipe – a method known in the Bible as chanak (to strangle) (Nah 2:13; cf. 2Sam 17:23).

One might assume that a carnivorous generalist and opportunist with such a wide prey spectrum always has plenty to eat. But surprisingly, the Bible often mentions the hunger of lions: “The young lions lack and suffer hunger…” (Ps 34:10); “The old lion perishes for lack of prey, And the cubs of the lioness are scattered” (Job 4:11); “The young lions roar after their prey, And seek their food from God” (Ps 104:21); “Can you hunt the prey for the lion, Or satisfy the appetite of the young lions?” (Job 38:39). These are accurate depictions. Starvation is, in fact, the most common cause of death for lions. While skilled hunters, they have an extremely high metabolism: over 60% of their body mass is muscle. Their daily food requirement is between 5–10 kg of meat. To meet this, they sometimes gorge up to 40 kg in a single meal and conserve energy by resting most of the day in the shade.

Despite all their adaptations, even small fluctuations in their environment can threaten their place atop the food chain. Inadequate nutrition reduces their performance – “it doesn’t lion,” so to speak – leading to a downward spiral. Risk of injury rises, as prey animals are not defenseless, and a weakened lion quickly ends up under a stampede. Some prides shift tactics: they prey on livestock – sheep, goats, cattle – and are often killed by shepherds (see 1Sam 17:34-36; Isa 31:4; Am 3:12). Others scavenge from hyenas, risking dangerous fights, or follow vultures to carrion. During these food shortages, cubs are neglected. They are the first to die when their mothers and the pride can no longer care for them.

It’s highly unusual for a predator to include humans as a main item on its menu – but lions sometimes do. Entire populations have, on occasion, systematically hunted people. This occurred, for example, when hoofed animals were intentionally eradicated from their habitats to stop the spread of rinderpest. Nobody considered what the lions would eat afterward. A similar situation may have occurred in the plundered and desolate Northern Kingdom of Israel, where God allowed lions to become a deadly scourge (2Kgs 17:24-26). Their presence is unmistakable: a lion’s mighty roar, reaching 114 decibels, carries up to 8–10 kilometers. However, lions only gain the ability to roar around age two – before that, they can only growl (Prov 19:12; 20:2; Jer 51:38).

The most infamous series of lion attacks due to man-made food scarcity occurred in 1898, when two lions killed 135 Indian and African railway workers within a few months, even dragging them from fenced camps along the Tsavo River in Kenya. While such numbers may be exaggerated, the terror these killer cats caused is easy to imagine. Often, there are clear reasons: half-blind, limping, or severely weakened loners have few options left. Very rarely, even healthy lions become man-eaters – once they discover how easy it is to kill an unarmed human (cf. Ezek 19:3-6). The Bible compares such danger to its most terrifying adversary: “Be sober-minded and alert. Your enemy the devil prowls around like a roaring lion looking for someone to devour.” (1Pet 5:8). The Greek verb katapino used here means “to swallow completely” or “gulp down like a drink.” Without strong protection like the “armor of God” (Eph 6:10-18), Satan – the “murderer from the beginning” (Joh 8:44) – could easily “slurp up” his victims.

When the lion appears on the opposing side, it symbolizes a powerful adversary. Naturally, this makes it a figure of the fallen creation – hostile to all living things, including humans – and even used by God for judgment (Judg 14:5; 1Sam 17:34; 1Kgs 13:24; 20:36; 2Kgs 17:25). This will only change in the future: “The young lion and the fattened calf will be together, and a little child will lead them … the lion shall eat straw like the ox.” (Isa 11:6-7; 65:25).

In a figurative sense, the lion often symbolizes hostile nations (Isa 5:29; Jer 4:7; 50:17.44) or human adversaries (2Sam 23:20; 1Chr 11:22; Ps 7:3; 10:9-10; 17:12; 22:14; 57:5; 58:7; Ezek 22:25; 32:2), frequently influenced by Satan himself – such as the cruel emperor Nero (2Tim 4:17). Paul describes his struggles in Ephesus using the expression etheriomachesa (1Cor 15:32) – “I fought with wild beasts.”

God Himself is also depicted as a roaring lion (Jer 25:38; 50:17). This image is ambivalent: He is the savior for His people, but judge and destroyer for His enemies. This duality is seen in how God will act through His renewed people – the “remnant of Jacob.” To those who welcome the Messiah’s reign, they will be as “dew from the Lord, like showers on the grass” (Mic 5:6). But to those who resist, they will be “like a lion among the beasts of the forest … who tramples and tears as he goes, with none to deliver” (Mic 5:7). Lion’s teeth are the ultimate symbol of terror (Joel 1:6).

The image of the lion becomes most powerful when applied to the Lord Jesus Himself. The mere presence of lions was a reason (or excuse) to stay at home: “The sluggard says, ‘There is a lion outside! I will be killed in the street!’” (Prov 22:13; cf. 26:13). Jesus knew there were “lions” waiting for Him on earth (Ps 22:14), and even God would meet Him like a lion in judgment for humanity’s sin (Lam 3:10). But He was neither lazy nor cowardly. He was diligent, persistent, courageous, and determined – leaving “His house” to willingly give His life on the cross, to save those who accept Him.

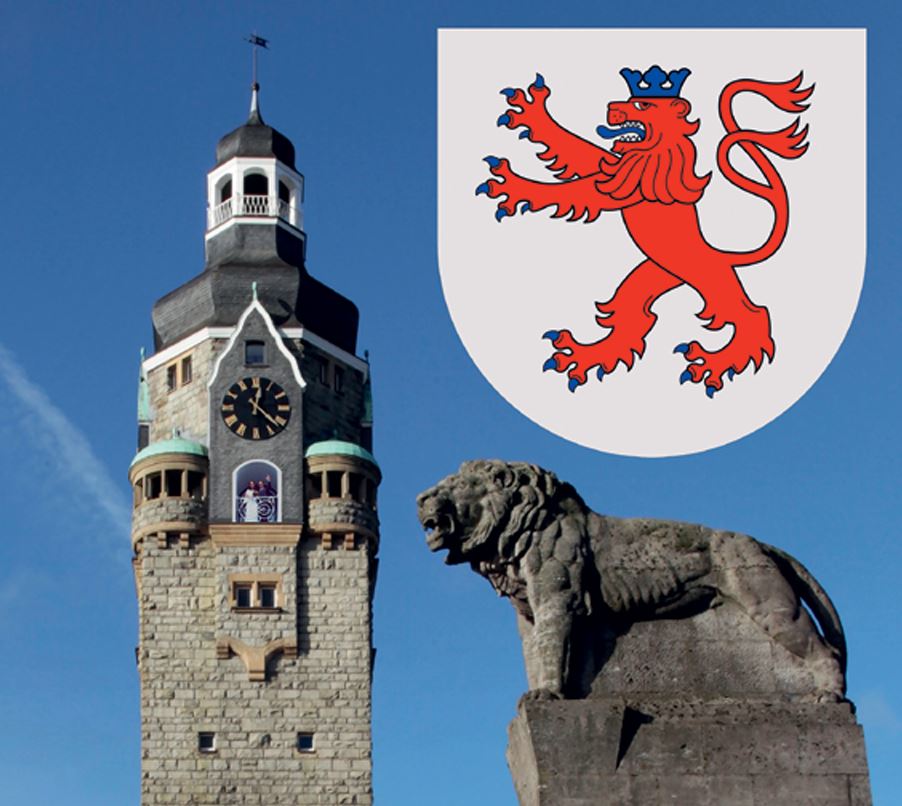

Power, aggression, dominance, upright posture, a flowing mane, a piercing gaze, and a bone-shaking roar – all these traits give the lion an awe-inspiring presence. He is predestined to symbolize sovereignty and is thus the most important heraldic animal in history.

In heraldry, specific terms apply: this lion is “rampant, with extended forepaws, and facing dexter” – a standard depiction. The blue tongue and claws (“armed”), red fur, and “divided and crossed” tail are not natural features of real lions but may reflect artistic conventions, even in antiquity.

King Solomon’s splendor surpassed all other kings. His lion throne, made of gilded ivory, was so magnificent that the Bible notes: “Nothing like it was ever made in any other kingdom.” (1Kgs 10:20). Seven lions stood on each side of the staircase leading up to his throne, with the final pair at the armrests. Clearly, Solomon saw himself – the great king – as the “chief lion” to whom all paths led. He echoed this image in his proverbs: “A king’s wrath is like the roar of a young lion, but his favor is like dew on the grass.” (Prov 19:12) “The terror of a king is like the growl of a young lion; whoever provokes him forfeits his life.” (Prov 20:2). The name Solomon means “peaceful,” and God gave him the special title “Jedidiah” – “Beloved of the LORD” (2Sam 12:25). Solomon is a prototype, a foreshadowing of the true King of Peace – Jesus Christ. In the four living creatures (Ezek 1:10; 10:14; Rev 4:7) that symbolize different aspects of the Lord, the lion face represents His kingship. When He assumes His rule, He will be revealed to all as “the Lion of the tribe of Judah” (Rev 5:5).

What was difficult for Jesus’ Jewish contemporaries (even His closest followers) to grasp was that prophecy also gave the coming Messiah a completely opposite symbol: “He was oppressed and afflicted, yet He did not open His mouth; like a lamb led to the slaughter, and like a sheep silent before its shearers, so He did not open His mouth.” (Isa 53:7)

While a lion fights to the last drop of blood when attacked, a lamb is helpless. A lion’s roar terrifies its enemies (Am 3:8), while the lamb is silent. How could these two contrasting images be fulfilled in the same person? It remained a deep mystery – until it was revealed in Jesus Christ: “What no eye has seen, what no ear has heard, and what no human mind has conceived – the things God has prepared for those who love Him.” (1Cor 2:9): He came to earth not to sit on a throne, but to be crucified at Golgotha – as the “Lamb of God” (Joh 1:29,36) dying for the sins of many. His journey led “from the lion throne to the lion’s den.”

To overcome evil, love, self-sacrifice, and grace had to come first – power and righteous judgment second. That’s why the most powerful image at the end of history is of the Lion appearing as a Lamb: “See, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has triumphed … Then I saw a Lamb, looking as if it had been slain, standing in the center of the throne.” (Rev 5:5-6). The slain yet standing Lamb symbolizes the crucified and risen Lord Jesus. Many mighty rulers have come and gone – but the Lamb’s nature is His defining and overcoming trait.

In His future Kingdom of Peace, the “Ariel” – the upper part of the altar of burnt offerings – will stand at the center of the great square temple complex for a thousand years (Ezek 43:15-16), a lasting reminder that Jesus, the true Lion, once sacrificed Himself voluntarily.

Who is the most powerful land predator? Who wins in a one-on-one fight: lion or tiger? This question fascinated the author even as a child. But there’s no easy answer. Let’s compare the contenders: both big cats are massive powerhouses, fighting with endurance, focus, and lethal intent. The tiger is clearly the “athlete” – more agile, faster, can jump farther, climb and swim better, and ranks higher in maximum size, weight, and raw strength. It has a wider jaw gape, longer canines, sharper claws, broader paws, and a larger brain. But the lion has greater bite force and delivers stronger paw strikes. A major advantage is the thick mane, which protects its vulnerable neck – the tiger’s favored target. Lions also regularly fight off rivals and take down large, dangerous prey on their own, whereas tigers prefer solitary ambushes and easier kills. Despite its smaller brain, many trainers who’ve worked with both species consider the lion to be more intelligent. With so many variables, it’s hard to declare a clear winner.

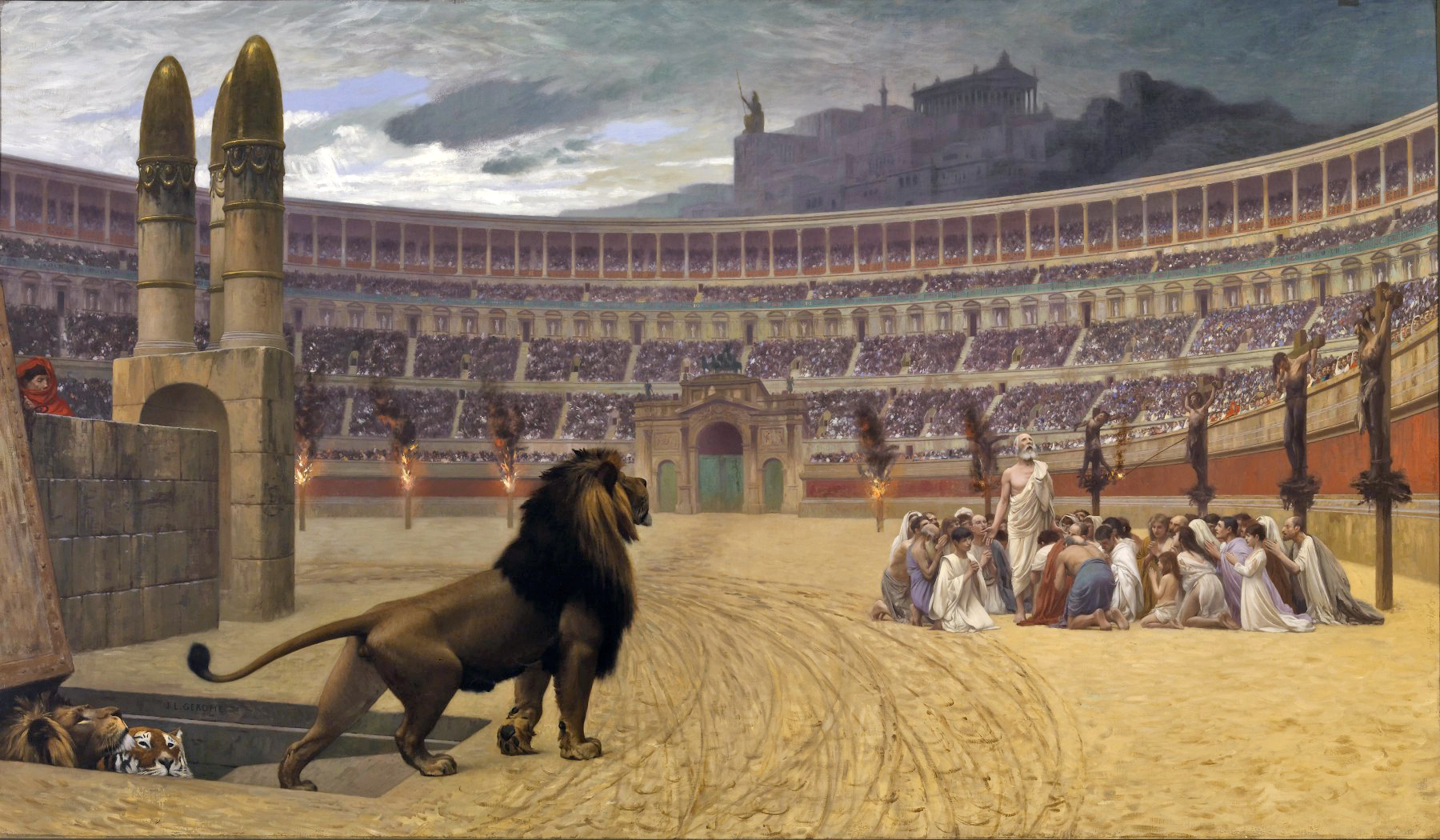

The Romans staged brutal animal fights in their arenas for centuries – sometimes featuring this very match-up. Historical accounts suggest they viewed the lion as the favorite. But context matters: they mostly used Barbary lions (Felis leo barbaricus), the largest lion subspecies, captured in North Africa. These often fought against Persian tigers (Panthera tigris virgata), a mid-sized subspecies. Indian maharajas also organized fights – between Bengal tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) and the smaller Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica). Unsurprisingly, they saw the tiger as superior. There’s even a larger subspecies – the massive Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) – which likely never encountered lions in the wild. Culturally, it seems Europe and the Middle East favored the lion, while India and East Asia favored the tiger, though India still features a lion on its national emblem. These cultural lenses probably shaped both how the animals were portrayed and how their fights were judged.

As fascinating as the debate may be, the outcomes of human-orchestrated battles offer little scientific value. Even within the same population, individuals vary greatly in size, constitution, and fighting experience. Adding subspecies variation only complicates things further. In zoos and circuses, clashes have been documented – but in the wild, such duels are extremely rare. Their natural ranges barely overlap, and they generally avoid one another. Furthermore, tigers are solitary, while lions live in social prides – the only cats to do so long-term. In a real confrontation, the whole pride would likely intervene on the lion’s side.

Sources:

Bro-Jørgensen, J: Evolution of sprinting speed in African savannah herbivores in relation to predation. Evolution 2013; 67:3371-3376; https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12233

Eklund, R; Peters, G; Ananthakrishnan, G: An acoustic analysis of lion roars. I: Data collection and spectrogramand waveform analyses. Proceedings from Fonetik 2011. 51:1-5; https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:541510/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Elliott, JP; McTaggart Cowan, I; Holling, CS: Prey capture by the African lion. Canadian Journal of Zoology 1977; 55(11):1811-1828; doi: 10.1139/z77-235

Futrell, A: The Roman Games. A Sourcebook. Malden, Massachusetts, USA (Blackwell Publishing) 2006

Haas, SK; Hayssen, V; Krausman, PR: Panthera leo. Mammalian Species 2005; 762:1-11; doi: 10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0. CO;2

Hammer, M: Rekonstruktion: Als Löwen Menschen fraßen. science. orf.at 03.11.2009; https://sciencev2.orf.at/stories/1631016/index.html

Hayward, MW; Kerley, GIH: Prey preferences of the lion. Journal of Zoology 2005; 267(3):309-322; doi: 10.1017/S0952836905007508

Kerbis Peterhans, JC; Gnoske, TP: The Science of »Man-Eating« Among Lions Panthera leo. Journal of East African Natural History 2001; 90(1)1–40

Kessler, G; Klinger, C; Meder, A: Lebendige Wildnis – Tiere der Afrikanischen Savanne (Löwen, S. 27-44). Stuttgart (Das Beste) 1992

Kohn, TA; Noakes, TD: Lion (Panthera leo) type IIx single muscle fibre force and power exceed that of trained humans. Journal of Experimental Biology 2013; 216(6):960–969; doi: 10.1242/jeb.078485

Linnemann, E: Gibt es ein synoptisches Problem? Nürnberg (VTR) 2012

Rapson, JA; Bernard, RTF: Interpreting the diet of lions. South African Journal of Wildlife Research 2007; 37(2):179-187; https://hdl. handle.net/10520/EJC117267

Skaggs, R: Lion and Lamb in the Apocalypse of John. Academia Letters 2020; Article 87; doi: 10.20935/AL87

Wilson, A; Hubel, T; Wilshin, S: Biomechanics of predator–prey arms race in lion, zebra, cheetah and impala. Nature 2018; 554:183188; doi: 10.1038/nature25479

Wroe, S; McHenry, C; Thomason, J: Bite club: comparative bite force in big biting mammals. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2005; 272(619-625); doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2986

World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF): Artenlexikon; https://www.wwf.de/themen-projekte/artenlexikon/loewe

Yeakel, JD; Patterson, BD; Fox-Dobbs, K: Cooperation and individuality among man-eating lions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009; 106(45)19040-19043; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905309106

Image credits:

Wildlife photos: Marc Walter

Wikipedia: Christenverfolgung Kolosseum / Jean-Léon_Gérôme_The_Christian_Martyrs’_Last_Prayer.jpg / Walters Art Museum // Bergischer Löwe – Remscheid / Remscheid_Bergischer_Löwe_02.jpg // Daniel in der Löwengrube / Daniel’s_Answer_to_the_King.jpg / allposters // Seringapatam Medallie / Seringapatam_Medal_obv.jpg / Lubicz